A programming note: a paid-only edition will go out on Thursday, with a look at recent Southern nature news. Subscribe now to make sure you’re on the list.

Today is, per the dictate of the National Caves Association, the official annual day to celebrate not just caves but also karst. Though I’m reluctant to (ahem) cave to these kinds of promotional holidays, I have been meaning to dig into karst for a while. So let us celebrate.

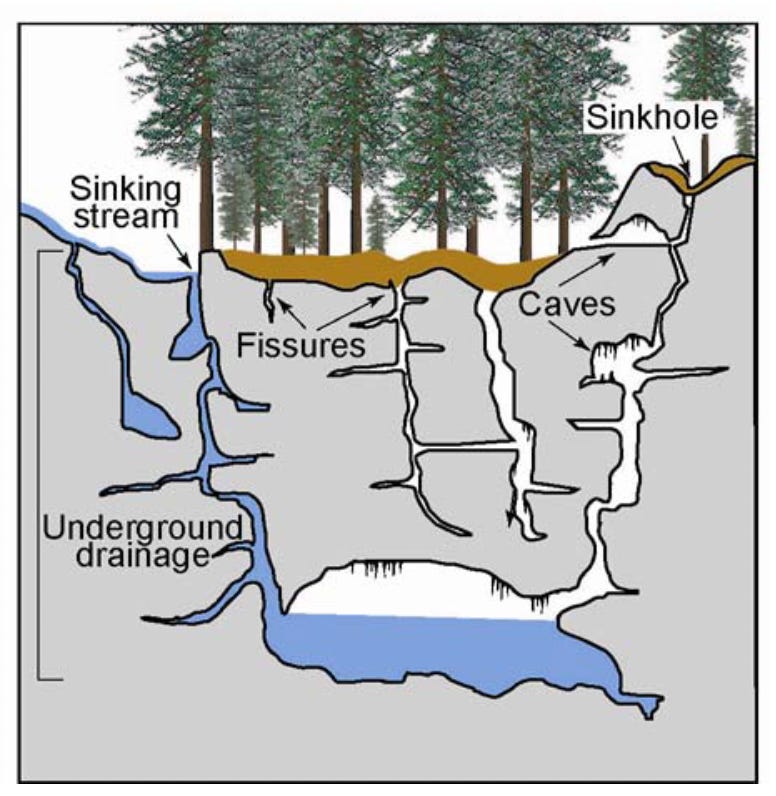

“Karst” is a landscape underlain by a secret terrain: vast networks of caves, “sinking rivers,” and other hidden topography. One key ingredient is the local rocks: you want terrain made up of carbonate bedrock is easily dissolved by acids. Limestone is the most common example: it’s a dense rock that is rent with fractures, which provide pathways for flowing water. The natural acidity in that water eats away at the rock, widening the cracks to form sprawling networks of underground caves. A low water table helps encourage karst formation, too, since it spurs the water to flow through the rocks, instead of just sitting there. If water hangs around too long within the limestone, it will absorb enough minerals to no longer be so corrosive.

Over time, as the underground caverns widen, the rocks above weaken and sink—and sometimes collapse. Whole rivers and lakes can disappear underground: not gone, just moved below the surface now, flowing through the hidden karst domain.

All this will be marked on the surface, too. Debris fills the sinkholes; forests emerge on top, growing about a topography turned rolling by all that sinkholes. Karst valleys are often dry, their streambeds empty of water, except after a downpour. Not that this is a desert. The valleys are dry because the rivers have gone underground. Kart landscapes often feature springs, as well as highly productive wells.

Karst landscapes underlie nearly a fifth of the United States, including much of the South. Florida, for example, though hardly famous for its topography, features plentiful karst. The state park system takes great advantage of this geology: you can see a seventy-foot waterfall plunging into a sinkhole or tour caverns or visit a cypress-ringed aquamarine karst spring.

Kentucky and Tennessee are hotspots, too. Mammoth Cave, in Kentucky, is the longest-known cave system in the world. Tennessee, meanwhile, has ten thousand identified caves, one fifth of all the known caves in the country—more than any other state.

The map below shows the expanse of karst across the U.S. Though one thing to keep in mind is that in some places—including much of Georgia and large chunks of Florida—the carbonate rock is buried deep under other, non-soluble materials, so you don’t get the same effect. (For a more detailed map, one too detailed to embed in this newsletter, head here.)

Caves tend to produce a unique ecology. Plenty of bats, of course, which thrive in that dank wet darkness. (They’re good to have, remember! They eat insects and pests.) Caves also tend to produce “troglobites”: blind and pigmentless creatures that develop other methods for navigating in pitch-dark caves. If they live in water, a troglobite is not as a stygobite. For example, in one corner Missouri and Arkansas, you’ll find a pallid little fish with no eyes, known as the Ozark cavefish.

He may be creepy, but we ought to be nice: the Ozark cavefish is endangered. This fish lives in just one cave system, which means a spurt of tainted water could spell its end.

Here we come to one of the perils of karst. Water collects in the caves, unsurprisingly—which is a good thing! The Floridian aquifer, a karst system, supplies drinking water to ten million Southerners. But since water flows so quickly and easily through karst formations, these are aquifers that don’t do much filtering. Contaminants flow great distances.

This was one of the reasons why when a few years back a massive pig farm opened along the Buffalo River, in Arkansas, many locals were worried about their beloved waterway: its underlain by karst, so the pig poop could easily taint the river.

The other obvious problem with karst are those pesky sinkholes, whose natural frequency can be easily increased by bulldozers scraping through the landscape, or heavy buildings laid on top. Florida has become an epicenter of the sinkhole phenomena. In 2013, a twenty-foot sinkhole opened beneath a man’s bedroom, and his body was never recovered. Karst is beautiful, but literally fragile—much like the wider world.

A quick tour of Southern karst

There are plenty of over-the-top tourist sites across cave country. Here are a few recommendations for a more natural experience.

Arkansas

I’ve already devoted a pin drop post to Lost Valley, a part of the Buffalo National River, where a short hike terminates in an underground waterfall. This is a lovely hike in one of my favorite expanses of karst.

Kentucky

As noted above, Mammoth Cave—with 426 mapped miles—is the largest known system in the world. The national park offers a variety of tours, from a two-hour overview to a six-hour in-depth expedition. There’s also plenty of surface-level landscape to explore if you want to see what karst looks like up top.

Tennessee

Lost Creek in Tennessee is named because it emerges from a collapsed cave, plunges down a waterfall, and then disappears underground again—classic karst behavior. The surrounding natural area also offers a stunning cave entrance that appeared in The Jungle Book. (Note that public caves in Tennessee are closed from September through April to protect endangered bats.)

Alabama

Jackson County has more troglobites than any other county in the United States. Watch out for some as you visit Russell Cave, a national monument that offers an archeological record that goes back ten thousand years.

Florida

As noted above, Florida’s state parks offer a number of karst-centric choices. You can, for example, climb down into an underground rainforest at Devil's Millhopper Geological State Park.

Georgia

Pettyjohn Cave, wild if well-trafficked, is known as a good choice for beginning spelunkers.