A quick note on programming: a subscriber-only edition will go out on Friday, delving further into how carbon sequestration fits into visions of Louisiana’s future coast. You can sign up here for full access.

There’s a wonderful moment on Interstate 55, on a drive south into New Orleans, when you cross an unmistakable boundary: just beyond the village of Pontchatoula, Louisiana, the solid ground gives way. You’re into the swamps.

This is a place where ancient geology is fully visible. Pontchatoula stands atop what are known as Pleistocene deposits—ground laid down more than 12,000 years ago, before the end of the last ice age. This is, in other words, a former beach, a coastline. The soggy soils south of Pontchatoula were all laid down in the millennia since the ice ages, in the Holocene, by the Mississippi River.

When the federal government arrived to build this highway in the 1970s, they chose the most solid terrain available. The interstate towers over a “land bridge,” a thin strip of land that was built by a former distributary of the Mississippi River roughly five thousand years ago. It’s known as the Manchac Land Bridge.

To the west of this land bridge there is a 90-square-mile waterbody known as Lake Maurepas. This is not really a lake, but an estuary—a place where the fresh waters of several rivers—the Amite and Blind and Tickfaw—meet the brackish water washing in from the sea. Since the land bridge keeps most of the salt out, Lake Pontchartrain, to the east—also an estuary—is more brackish. Thus, the Manchac Land Bridge helps sustain freshwater cypress forests along the southeast edge of Lake Maurepas. These constitute the second-largest contiguous swamp in the state of Louisiana.

This lake sits far enough from the infamous “Cancer Alley” that, until recently, it’s avoided much of an industrial buildout. Now, though, a company called Air Products wants to pipe carbon dioxide from a planned hydrogen plant in Burnside, Louisiana, twenty miles west of the lake, so that it can be pumped past the mud lake bottom, into the underlying bedrock—a supposed climate solution. “Subsurface seismic survey work” is currently underway, despite the fact that the proposal has prompted fierce opposition, even from locals who generally support the oil and gas industries.

This is beloved territory. The Maurepas swamps were once known as a duck-hunting heaven; videos compiled here in the late 1980s helped launch the famous A&E series Duck Dynasty. Even then, of course, these forests were not pristine: loggers swept through the region, and all of Louisiana, in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The ghost town of Ruddock, which lies along the land bridge, was once home to one of the country’s largest sawmills. The land bridge itself was eventually all but denuded. There are a few old giants in the Maurepas swamps still, trees that were already hollow and therefore passed over. Most of the forest, though, is second-growth.

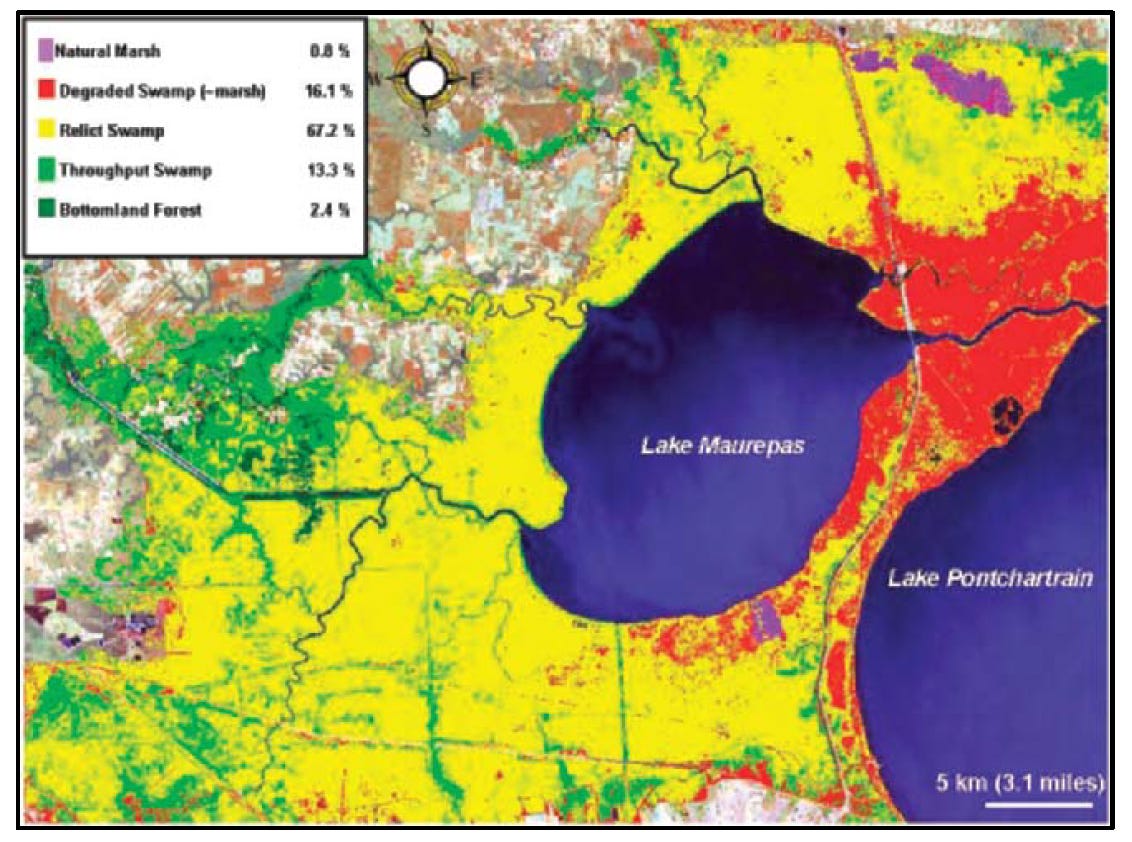

Lately, regeneration of new trees has been nearly nonexistent. That’s due to a tangled nexus of problems, including a lack of sediment: the levees along the Mississippi River prevent new mud from arriving, so the land is slowly sinking, and the ground is flooded so often that it’s difficult for new trees to grow. Saltwater has crept in from Lake Pontchartrain. Invasive species—nutria and salvinia especially—have arrived. Now the ducks, too, seem to be scarce: as Jonathan Olivier noted in a 2019 essay in Country Roads, in 2018 only 270 ducks were harvested in a local wildlife refuge, despite 600 attempted hunts.

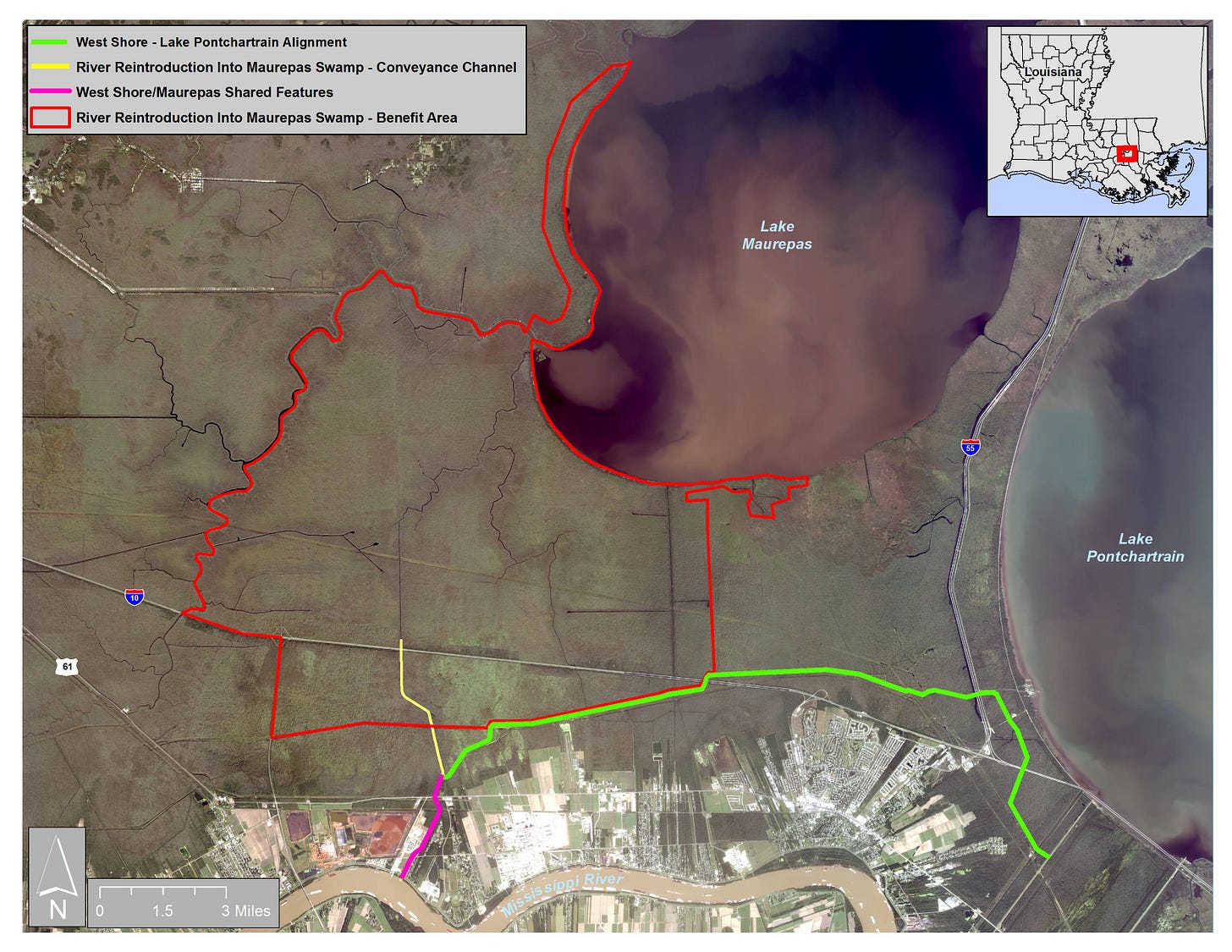

There is some good news for the Maurepas swamps: work will begin this summer on a freshwater diversion, which will carry Mississippi River water into the forests, helping restore some natural hydrology. This diversion is much smaller than the controversial project coming to Plaquemines Parish, and has met less opposition. Still, it’s taken twenty years to get the diversion off the ground. Its liftoff is mostly thanks to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ decision to classify the diversion as a mitigation project, an offset against the damage caused by a levee. That helped shave down the state’s responsibility to pay for the infrastructure.

But as it receives this new lifeline for its swamps, Lake Maurepas itself is being invaded, locals say.

Gov. John Bel Edwards is attempting to position Louisiana as a leader in the emerging field of carbon sequestration: carbon emissions can be piped deep into the ground and thus kept out of the atmosphere. Air Products, one of the companies lured by Edwards’ overtures, wants to build a hydrogen plant in Burnside, a small town along the river. They’ve decided Lake Maurepas is an ideal site to dispose of their carbon waste, in part because there are so few other pipelines nearby to get in the way. That means carbon pipelines would run through twenty miles of the Maurepas swamps before terminating in wells deep in the bedrock.

Environmental groups are, unsurprisingly, opposed to this project. As they note, studies suggest that the kind of hydrogen plant that Air Products wants to build will, even with sequestration, be a net problem for the climate. One 2021 study suggested that emissions will be 20% higher than burning coal, in part due to the energy needed to fuel the capture of the carbon itself.

Because there are still crabbers and fishermen who work this lake, local politicians—often conservative politicians supportive of oil and gas, and sometimes skeptical of climate change—are up in arms, too.

Last December, Air Products hosted what was supposed to be a demonstration of how harmless their exploratory process is. Locals watched as officials Air Products detonated several pounds of dynamite. The explosion was, as promised, invisible from the water's surface. But what many noticed was a security guard wearing tactical gear, an assault rifle slung over his shoulder. Air Products later noted that this was an off-duty sheriff's deputy, whose presence was standard protocol. Still, the man with a gun only underlined the sense that one of the last untouched zones adjoining Louisiana's petrochemical corridor was under invasion.

If you want to learn more about the legal efforts to block Air Products’ project, and how it fits into the larger discussion around carbon sequestration, be sure to sign up for the paid edition of Southlands. A follow-up to this newsletter will arrive on Friday.

If you go

Though seismic testing is underway on the lake, the surrounding wetlands remain a wonderland for adventurous explorers. If you’ve got your own vessel, consider launching from what one Google Map user has labeled as “Kayak Heaven.” (Google Maps is filled with gems in these parts, including this supposed “night club”—which is, according to one reviewer, “a little damp.”) Southeastern Louisiana Paddling has a good overview. In recent years, nearby parking has been blocked at times, but was open as of December 2022.

Another beloved spot in the Maurepas Swamps is the Our Lady of Blind River Chapel, which is accessible only by boat. Once again, check out Southeastern Louisiana Paddling for details.

No boat? No problem. There are a ton of kayak tours available in both the Maurepas Swamps and, along the land bridge, the Manchac Swamps. (If anyone has experience with these, please chime in in the comments!) Or grab a seat at Middendorf’s, which sits along the pass where Lake Maurepas empties into Lake Pontchartrain, for a platter of thin-cut fried catfish along the water.

I am familiar with the seismic survey world but I don't think I have ever seen an armed police officer at any of these surveys. It makes me wonder what is up with this one that one is needed.