Late last summer, reporter Mike Smith noted in a story for The Advocate that the chatter on YouTube channels and radio programs devoted to Louisiana fishing had turned to redfish: suddenly, this famous species seemed a lot harder to find.

The science behind the decline was murky—whether the fish really were in decline was not fully clear—in part because the last time the state of Lousiana had formerly assessed the state of redfish “stock” was in 2004. Biologists from the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries heeded the worries, though, and commenced a new study.

In December, they announced their slightly confusing conclusion: while this species isn’t yet overfished, overfishing is occurring. A better way of saying that might be that while redfish aren’t yet doomed, they’re well on their way to being fished into oblivion. In 1994, there were an estimated eight million one-year-old redfish living in Louisiana’s inshore marshes. Now, that population has declined to 1.5 million. And only one in five of these young redfish are expected to successfully migrate offshore to spawn—well below the target rate of 30 percent.

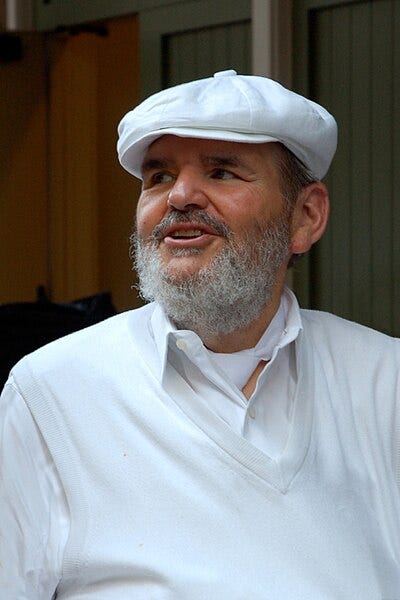

Redfish is closely associated with Louisiana. That’s in part thanks to famed chef Paul Prudhomme, whose recipe for blackened redfish became a sensation in the 1980s. It’s also because Louisiana has long allowed anglers a longer leash than other Gulf of Mexico states—permitting a higher daily catch limit, in particular.

The idea was that these fish were so abundant in Louisiana’s maze of marshes that sport fishers could be cut loose. Now, though, state biologists have decided that to save the redfish, Louisiana’s annual catch needs to be reduced by more than a third. Earlier this summer, the Department of Wildlife proposed new regulations, including tightened catch limits, more in line with the rest of the region.

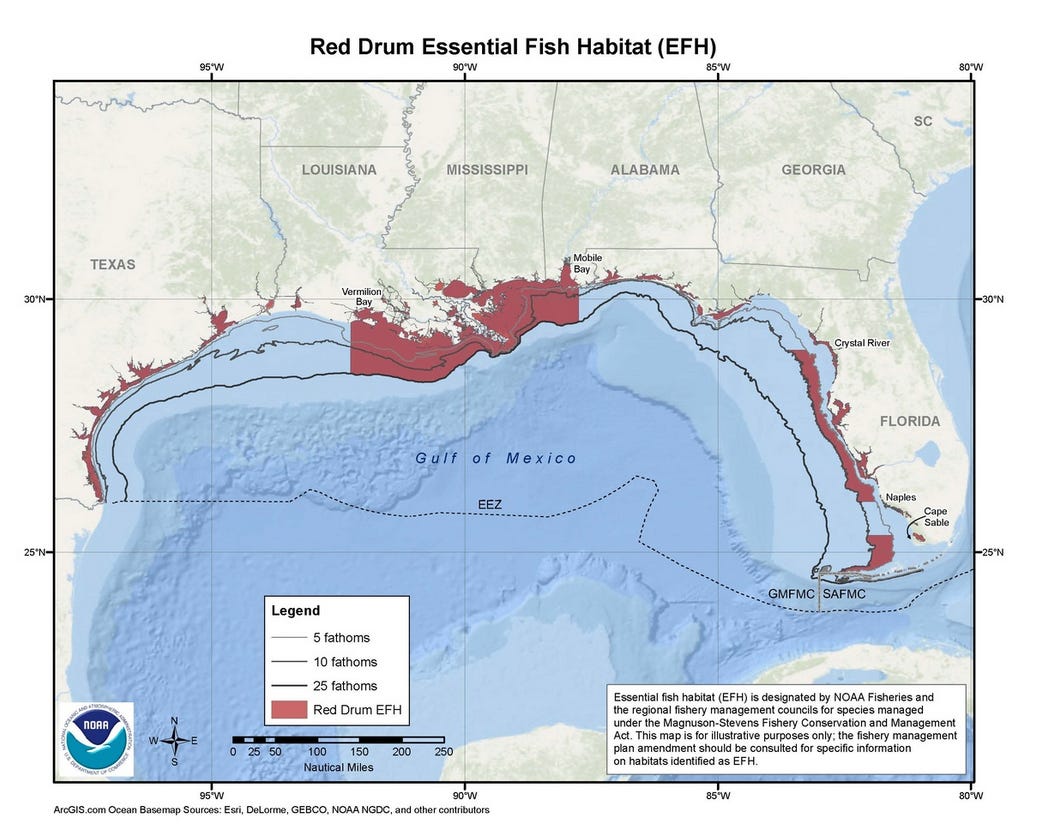

Scianenops ocellatus, known as redfish in Louisiana, is also called red drum—a name reflects the way male fish beat their muscles against their inflated swim bladders to attract mates. are, yes, slightly reddish on their backs, and white on their bellies, and are best distinguished by the eyespot (or sometimes eyespots) on their tails, which may be a trick that convinces predators to attack the wrong end of the fish. They can be found as far north as Massachusetts, but given that young fish like seagrass beds and muddy bottoms, the Gulf of Mexico—and Louisiana in particular—offers essential habitat.

One good place to begin the story of the red drum is in the French Quarter, in 1980, where famed chef Paul Prudhomme had just opened his restaurant K-Paul. He’d been cooking redfish for years, often over open flames. But, lacking a grill in the K-Paul kitchen, he tried something new: he dipped the fish in butter, dusted its skin in cayenne and herbs, then seared the filet in a cast-iron skillet. It was a culinary experiment that changed Prudhomme’s life—and the Gulf of Mexico.

“It seemed like within days the restaurant was full,” the chef later remembered. “Within weeks there were huge lines.” Quickly, chefs across the country attempted to emulate the dish: every menu seemed to feature blackened Cajun something; jars of Prudhomme’s “magic” spice blend were available on grocery store shelves for cooks who wanted to try the technique at home.

Redfish, too, surged in popularity—in New York City especially. As Louisiana’s catch was shipped north, a once-middling fishery boomed.

The federal government soon realized this fish could not survive its sudden popularity, and instituted a temporary ban on commercial fishing. That became permanent across most of the Gulf of Mexico, though a small commercial harvest is still allowed in Mississippi.

Today, you can still find redfish on menus across New Orleans—a supposed connection to the state’s longstanding connection with its oceans. The story is, as always, more complicated.

First, there’s the fact that before its sudden fame, red drum had been known mostly as a trash fish—the sort of thing you’d eat because you caught it and couldn’t afford to buy something else. Prudhomme’s cooking was untraditional, anyway, merging his family’s humble Cajun traditions with the urban Creole cuisine of New Orleans.

Of course, the other issue with redfish as a symbol of Louisiana is that, given the commercial ban, this fish must come from elsewhere. There are aquaculture ponds in Texas, but most redfish is now imported from farms in Asia.

If redfish is not a signal of Louisiana’s long connection with the sea, then what is it? Mostly, I think, a reminder of how down here we like to have a good time outdoors. Adult redfish can live up to 40 years; the largest fish ever caught weighed 94 pounds. It’s a fun fish to fight, then. Just in travel costs in Louisiana, this fish generates $500 million in revenue each year.

As I noted above, Louisiana red drum regulations have been pretty loose, in part because—in an ironic but typical fashion—the slow disappearance of the Mississippi River delta was good for this fish. Red drum is one of many species that like so-called “edge” habitat, the places where the marshes meet open water. The fragmentation of the marsh meant more and more edge.

The idea that coastal land loss will lead to ecological collapse is a well-founded theory—but it’s always been something we expect to see in the future. Other species, too, like shrimp, have so far benefitted from the fragmentation. Now, perhaps, the decline of redfish could be a signal that a tipping point has finally arrived. Though it’s important to note that the science is not yet settled.

The state, collaborating with the conservation nonprofit CCA Louisiana, has launched an experimental stocking program. The initial goal is to raise 10,000 fish in a hatchery, which will be released in Calcasieu Lake—a test to see if hatchery-raised redfish can survive in the wild. The catch reductions, meanwhile, are open to public comment through early October; if the public and state legislators prove amenable, the limits could be in place before the end of the year.

Want to try it?

If you want to eat wild-caught Louisiana redfish, you’ll have to get some yourself—or at least find someone who has caught one. (You may have better luck in Mississippi restaurants, since, as I noted above, the state’s commercial fishers are allotted a catch of 60,000 pounds a year.) If you do get your hands on some redfish, though, the New York Times offers an adapted version of Prudhomme’s recipe.

Around the Southlands

Louisiana

The big nature news last week was that, after years of debate and study, the state finally commenced construction on the first major “sediment diversion” on the Mississippi River—a $3 billion project meant to rebuild 21 square miles of land. (WWNO)

+ In the meantime, a different kind of resource has begun sprouting in the marshes: storage facilities for liquid natural gas. (Grist)

+ The Washington Post offers an immersive, multi-media look at land loss in Louisiana.

Planning has begun for trail repairs in Jean Lafitte National Preserve. (National Parks Traveler)

Art & climate

The delicate art of writing about climate change (Sea Change/WWNO)

North Carolina

A legal settlement could prompt the release of more red wolves into the wild. (The News & Observer) [Ed. note: My early take, after glancing over the settlement, is that this feels fairly toothless. For more on the topic, see Southland’s look at red wolves.]

+ Just days after that settlement, a wolf was shot and killed. (News & Observer)

Mining company officials face “skepticism and anger” over their plans to restart an open-pit lithium mine near Charlotte. (Reuters)

Georgia

A federal judge has granted a mining company’s request to transfer a dispute over the Okefenokee Swamp to Georgia. (Bloomberg Law)

Florida

What’s it like to swim in a 100-degree ocean? (New York Times)

+ DeSantis touts his convservation credentials—but has said nothing about the heat that is killing the state’s marine ecosystems. (HuffPost)

Endless development has Florida environmentalists at odds over how to protect panthers. (Heatmap)

A Floridian abundance of bears. (Garden & Gun)

In Miami, the prevalence of conch underlines a Caribbean connection. (Gravy)

Virginia

The National Park Service is developing a management plan for its popular “triple crown” of peaks. (National Parks Traveler)