Field Guide: The Pearl darter

A threatened fish—and its threatened namesake river—offer reminders of the precarious biological wonders in the South

Quick programming note: paid subscribers will receive a roundup of recent news on Thursday—and, as always, receive complete access to the archives.

The facts I can share about the Pearl darter are rather limited.

The most salient fact, really, is that there were only two watersheds where this little ray-finned fish ever lived. And that’s part of the problem now: the Pearl darter has become a rare enough species that much of our knowledge must be drawn from other fishes. But its historical habitat, in Mississippi’s Pearl and Pascagoula river basins, features sandy bottoms, rather than gravel. Other darters in other river systems aren’t always great stand-ins for our little fish.

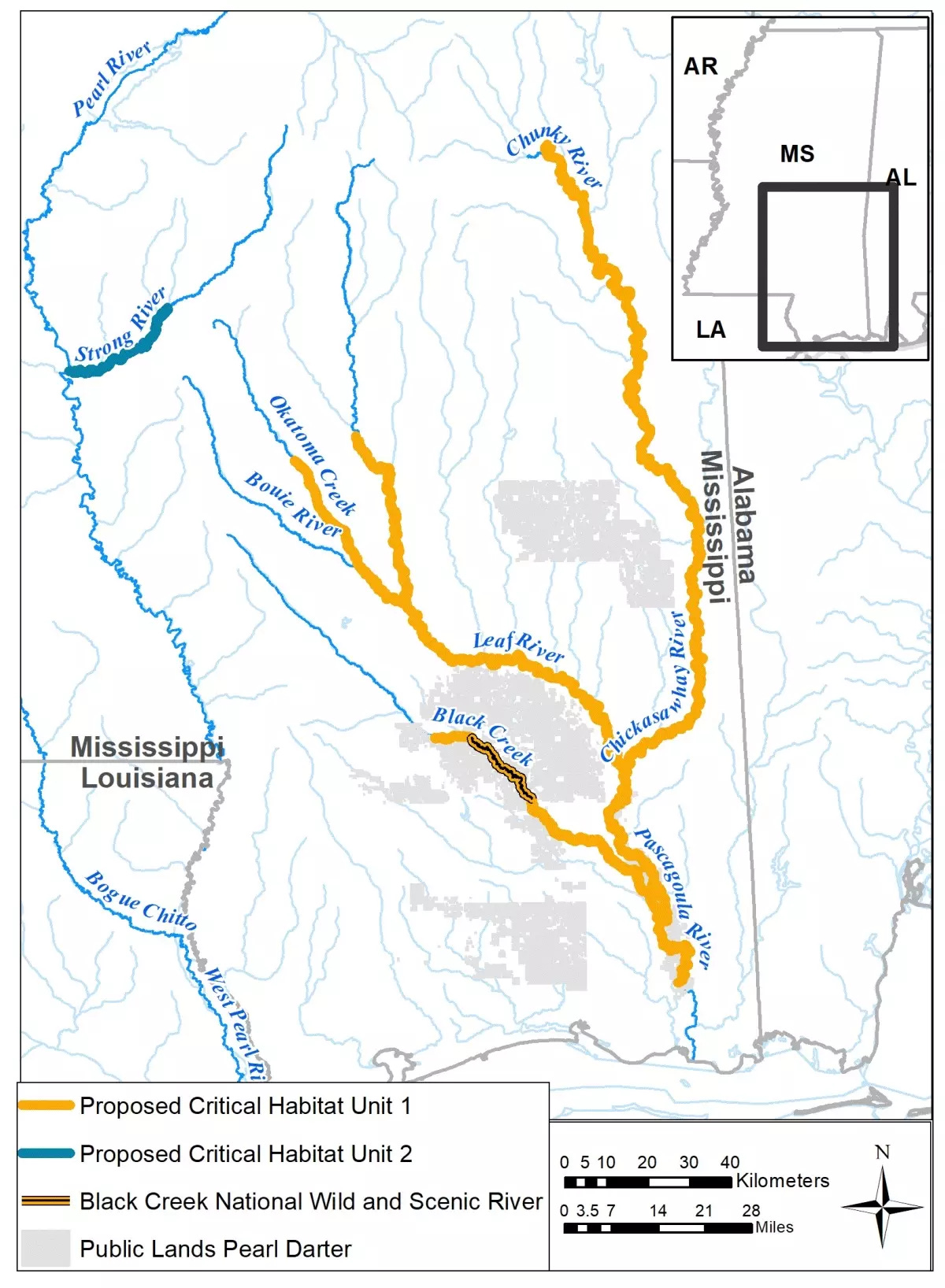

The Pearl darter was officially listed as a federally endangered species in 2017. Back then, though, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wasn’t quite sure what rivers should qualify as its “critical habitat”—the geographic areas deemed essential to its ongoing conservation. Finally, earlier this month, after years of consultation with local biologists, the USFW has designated 524 miles of rivers as critical habitat for the Pearl darter.

This is a win for the fish, though a minor one. The designation simply means that before a federal agency can undertake work, it must consult with federal biologists. If private landowners receive federal funding for projects, they, too, must consult.

“Protecting what’s left of their habitat gives Pearl darters a fighting chance,” Will Harlan, the Southeast director at the Center for Biological Diversity said in a press release. “Dams and pollution have hammered these tiny fish, but they’re still clinging to survival in these key rivers.”

The first scientific descriptions of the Pearl darter weren’t published until 1994. They were largely based on old specimens drawn from the Strong River, a tributary of the Pearl River—which is how the fish got its name. By the 1990s, though, the darter had already been absent from the Pearl for nearly twenty years.

These fish faced various problems, most of them obvious: the Pearl runs past Jackson, Mississippi, so in addition to pollution and sedimentation, there has been significant engineering, including the construction of a major reservoir and the installation of low-head dams. (The Pascagoula, where the fish still survives, is, not coincidentally, the largest mostly unaltered river system in the lower 48 states.)

On the map above, you’ll notice that a portion of the Strong River has been declared critical habitat—despite the fact that the fish doesn’t currently live there. This is typical: the idea is that this habitat might become occupied by the fish, ensuring its survival by spreading beyond its current territory. USFWS found that the Strong River includes many desirable qualities for this fish, including, as they wrote in the critical habitat designation,

a stable channel with bottom substrates of fine and coarse sand, silt, loose clay, coarse gravel, fine and coarse particulate organic matter, and woody debris; a natural hydrograph with flows to support the normal life stages of the pearl darter; and the species’ prey sources.

It’s also promising that other species that were once in decline in the Strong River, including the frecklebelly madtom and the crystal darter, appear to be increasing again.

It’s worth noting, though, that the nonprofit American Rivers last week named the Pearl the country’s third-most-endangered waterway. That’s thanks to a controversial flood-control project that has recently received an infusion of federal cash. American Rivers and other critics call the “One Lake” project a “private real estate development scheme masquerading as a flood control project”—an effort to give wealthy landowners a fancy new lake.

The One Lake project would sit upstream of the confluence of the Strong and Pearl rivers; the project won’t be impacted by the new critical habitat designation. But if the fish does take hold again in the Strong, the new lake would not offer favorable habitat for its further spread. “The proposed One Lake project does not appear to be helpful for the Pearl darter's recovery in the Pearl River basin, one of only two basins where it has historically occurred,” Harlan told me, by email.

Some people might struggle to sympathize with the Pearl darter: these are tiny fishes, less than 2.5 inches long, that humans don’t eat them. If they wink out, gone from their home rivers, what would really change?

To me, though, the Pearl darter offers a reminder of how rare a patch of Earth I live upon. Some 6,200 native plants grow across the “Geological Coastal Plain”—one name for the swath of land that runs along the southern edge of this continent. Many—29%—are endemic, meaning they grow nowhere else. The numbers are similarly staggering for other lifeforms: of the more than 100 amphibians that live here, 47% are endemic.

The region’s rivers are especially rich, featuring 424 species of fish, nearly a third of which are endemic. “Southern rivers are the most biologically diverse in the temperate world,” Harland noted in the press release. Even among conservationists, though, this bounty is often ignored.

A decade ago, a group of biologists highlighted the coastal plain as an overlooked biodiversity “hotspot.” This is an officially defined concept, meant to highlight biologically rich places on the verge of disappearing: a hotspot must feature more than 1,500 endemic species and losses of habitat over 70%.

The biologists noted several reasons why the Southeastern plains are so often forgotten: there’s a myth that this region is too young, or too climatically unstable, for so many species to have evolved. That strikes me as a rather high-level mistake, one it’s only possible for someone already versed in paleoclimates and evolutionary theory to make. More pertinent to the masses, I think, is the fact that these plains are far flatter than other biodiversity hotspots. The terrain here rarely rises higher than 800 feet. That’s uncommon among hotspots. But the habitat here has been shaped by millions of years of fires and floods, producing an amazing abundance of creatures. Every new project we install in rivers offers a new threat to that biodiversity.

To see it

The Pearl darter may not be the world’s most charismatic species, but it offers an excuse to explore this region—and the Strong River especially, which, one can hope, may become a future stronghold for the threatened fish.

The Strong is not named for its flow but for its tannic flavor. The town of D’Lo, which sits along the Strong River, got its oddball name for similar reasons: on old French maps, the river was apparently labeled “de’l’eau sans potable,” or of water nonpotable, which was eventually shortened into a new form.

D’Lo is known today for its state-run “water park,” which sits just within the upstream edge of the Pearl darter’s new critical habitat. The park is built along a set of shoals and features a riverside cabin as well as campsites. You can also rent canoes and kayaks and arrange for a shuttle for a one-way trip. Check the river gage: you’re looking for water between three and five feet.

I always find it fascinating how long it takes USFWS to agree upon and come up with critical habitat and reasons why other species never get the designation. I hope this designation will help the Pearl darter and subsequently work to protect the river!

And to your point about the south's biological diversity, it's why I can't find myself able to want to move anywhere else. We have so much wonderful, overlooked habitat and wildlife that you can spend a lifetime getting to know the region and still not see it all.