As a foggy twilight descends on Birdeye, Arkansas, the last rays of sunlight are swallowed by the hulking mass that is Crowley’s Ridge—a sliver of uplands that cuts through 200 miles of Missouri and Arkansas.

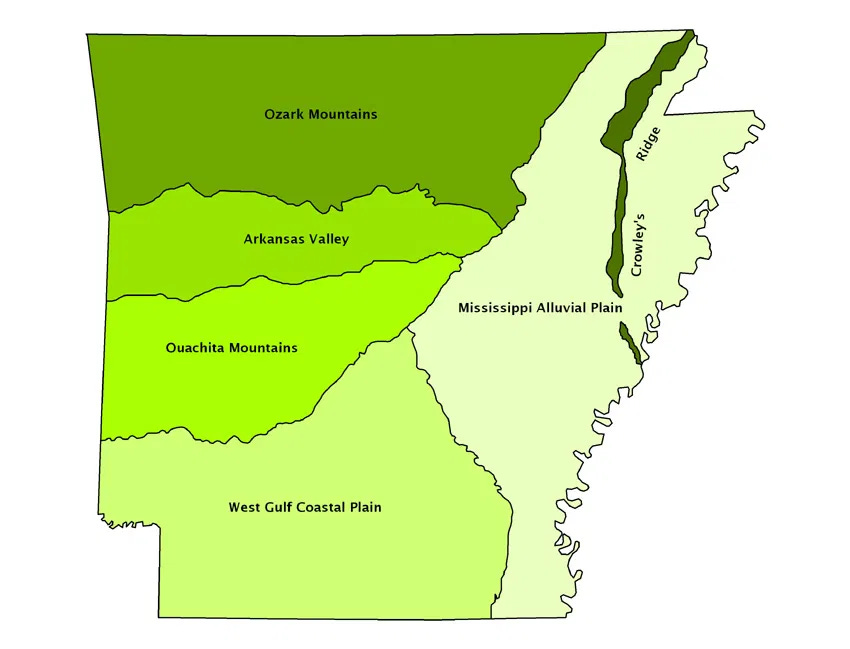

As Arkansas elementary school students are taught, Crowley’s Ridge is the smallest of the state’s six natural provinces—a formation is so unusual that its only geological counterpart exists in Siberia. It’s surrounded entirely by another province, the Mississippi Alluvial Valley, which you’re more likely to know as the Arkansas Delta.

As Tim Schuler noted in a great recent essay in Places, “even among Arkansans, the delta is often unseen.” Count me a rarity, then; I crisscrossed the region for work throughout the decade I lived in Mississippi; I spent several in the delta there while reporting my book The Great River. Until last month, though, I’d spent almost no time along Crowley’s Ridge, mostly because no one had given me a reason to.

I jumped, though, when a nonprofit called studioDRIFT invited me to read from the book at the third annual Birdeye Gravel Festival. Their goal is to take this lost Delta and turn it into a recreational destination—thereby bringing new money into communities and creating sustainable ecosystems, too. Their marquee project, for now, is the Crowley Ridge’s Gravel Trail—249 miles of roads, dirt mostly, that include nearly a mile and a half of climbing, a stunning sum in the flatness of Arkansas.

Crowley’s Ridge, which stretches for two hundred miles in a broad arc through two hundred miles of Missouri and Arkansas, has long been a place of geological mystery: There’s still-unsettled debate over whether it was formed by the upward thrust of plate tectonics or the downward power of erosion scraping clean the surrounding land. (The best current answer is, actually, both.) We do know that the highest ground on the ridge consists of ancient, wind-blown soils that settled here some twenty-thousand years ago; because this dirt, known as loess, is easily eroded, the ridge is pockmarked with gullies and hollows. The forests here, filled with oak and hickory, are the westernmost example of an ecosystem otherwise seen in Appalachia.

The ridge’s name comes from Benjamin Crowley, who in 1821 became the first known American citizen to establish a homestead here. “Good enough,” he apparently told his son upon finding the site. The ridge was a rare bit of high ground amid a swampy inland sea. Within the next century, though, thanks to railroads and loggers and drainage canals, the swamp was conquered, denuded and drained—“rationalized,” as Schuler puts it—into fields of cotton and soybeans and rice.

My last long bike ride was several years—and medical procedures—ago, but when I visited I nonetheless packed my bike so I could join a 60-mile ramble. We rode first along delta levees and then crossed the ridge, twice. All day the sky was a film of water that turned at times into frigid spittle. My tires were nearly too skinny for the mud. For days after the trip, my muscles screamed at me. But I’d found something new there—an irruption of wildness amid the agricultural expanse, a great hulking expanse of forest. That night, my legs throbbing, in the settling darkness it struck me as a domain pulled from folklore, still haunted by the ghosts of the wolves who once wandered these hills.

Want to read more about studioDRIFT? Their work will be profiled in the first print issue of Southlands, coming this September. And don’t forget to tag us in your Instagram photo captions with @southlandsmag so we can reshare your views of the wild South!

In season

Garden & Gun >>> Jim Beaugez lodges a recommendation for a winter-time visit to Alabama’s Sipsey Wilderness.

Garden & Gun >>> HOW TO: Watching for birds in Southern backyards.

Not all news is bad

The Assembly >>> Hot Springs, North Carolina, a mountain tourist mecca, hopes to reopen by spring.

Garden & Gun >>> For more than a century, Georgia’s state flower has been an invasive rose. Now, the sweetbay magnolia could seize that title.

The Assembly >>> Can the seeds of an iconic Southern veggie become the next big oil?

Cause for concern

The Georgia Virtue >>> The company that aims to mine titanium next to Okefenokee says that a refuge expansion will not alter their plans.

Sierra >>> Blue crabs, one of the South’s most famous seafoods, have long been in peril.

Grist >>> As people flock to paradisical Florida, a lack of water is becoming a worry.

Wall Street Journal >>> There is a “glut of pine” in the South, thanks to decreased demand for pulpwood. One controversial fix for forest owners? Sell the wood to new wood-burning electrical plants—whose claims of environmental gains are hotly contested.

Amen and amen.