"...this world is the only one we've got..."

Essayist Martha Park on the apocalypses we imagine in the South

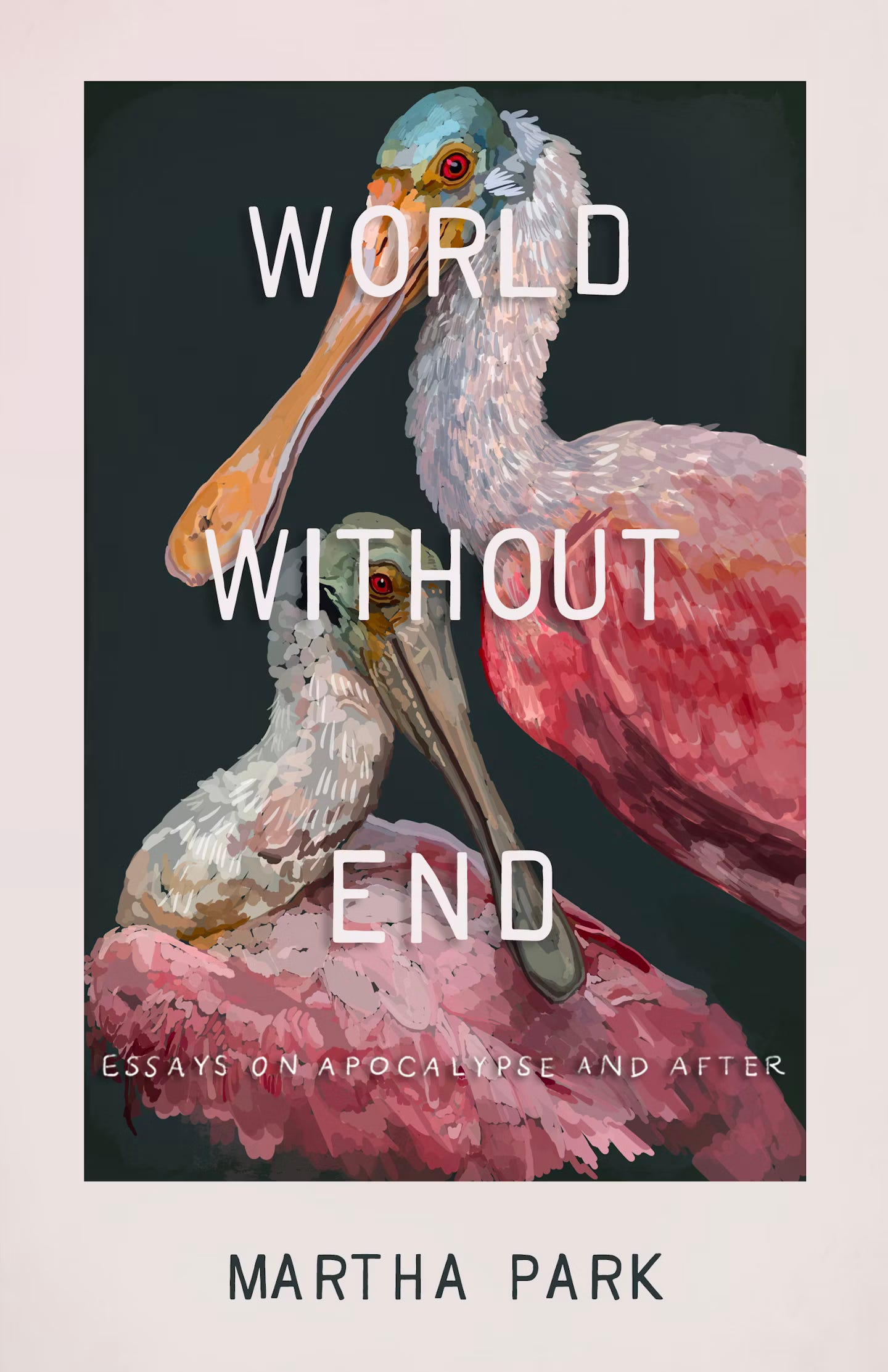

I’ve been reading Martha Park’s writing for years. So when I saw that her first book was forthcoming—World Without End: Essays on Apocalypse and After, it’s called—I knew I had to get my hands on a copy. And when I started reading an advanced copy a few months ago, I began thinking immediately, Wow, this is the kind of work I want to publish in Southlands.

Martha’s writing does what the best essays do: She weaves together big ideas; she pushes readers into territory they might not realize they’re headed towards. She raises questions and then, gracefully, lets you, the reader, answer them yourself. And she’s exploring Southern nature from a perspective quite different than my own: As the daughter of a Methodist preacher, she’s considering how Christianity had shaped her vision of nature.

We discussed running an excerpt from the book in the magazine, but when that didn't work I went for the next best thing: I got on the phone with Martha to talk about faith and environmental stewardship, the texture of Southern landscapes, and what it means to love a world that might be coming to an end. Read it all below the fold, and then go get your copy of World Without End, which is out now.

—Boyce

Going Deep

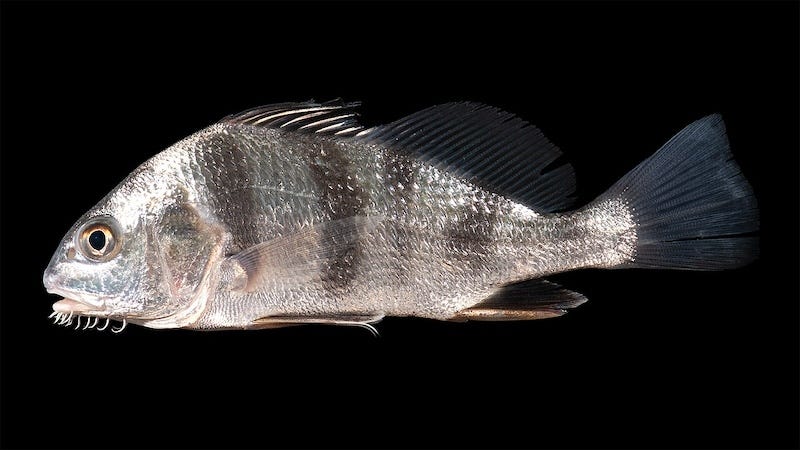

Days of the Drum: As she prepares to say goodbye to a little parcel of the Virginia coastline, a writer finds solace in the humble black drum.

+ Not feeling fishy? The orange, too, can be a reason for hope.

Duck Decline: I’ve linked already to articles centered on Arkansas, but in North Carolina, too, the birds are under threat thanks to a “perfect storm”: rising seas are swallowing marshy habitat while avian influenza is savaging populations.

+ Downeast in North Carolina, “climate change” is considered “dingbatter” language.

Lowdown

New details emerge in the tit-for-tat over Louisiana’s contentious land-building project. // It took more than a week, but a leaking oil well in the Gulf has finally been plugged. // The New York Times dives into the crisis surrounding Gulf shrimp. // Want a bit of Mississippi’s wild Horn Island? A piece is, apparently, is for sale. // A tick-borne illness is flaring in the mid-Atlantic.

Martha Park on climate, apocalypse, and writing Southern nature

Boyce: There's a constellation of motifs and ideas and concepts that you keep returning to throughout this book. But you narrowed down to a subtitle: “Essays on the Apocalypse and After.” How did you settle on that?

Martha Park: I was ery newly home from the hospital with my daughter, and [my publisher] Hub City emailed me and was like, ‘We need to change the title of the book.’ They basically said, ‘There's too many other books with this title. It's gonna hurt your SEO.’ And I was like, ‘Well of course there's other books with this title—it’s from the Gloria Patri.’ It's a commonly held phrase, which is why I wanted to use it. So we decided to keep the title and add a subtitle.

There have been lot of books with apocalypse in the title or subtitle lately, and I wanted the subtitle to indicate my complicated relationship with the idea of apocalypse. So I thought adding “and after” was helpful. It suggests that there isn't one end to the world that we are anticipating right now—that there isn't like a God-sent end of the world that we can anticipate, and yet there is the sense that worlds are ending all around us, all the time.

B: What drew you to ‘apocalypse’ as a unifying concept?

MP: I wrote a book that’s kind of scattershot, so it was hard to pin it down to a singular thing. But despite its meandering, the book really is centered around conceptions of apocalypse. I’m trying to understand the God-sent, world-ending apocalypse that my husband grew up with in the evangelical church, which stems from a particular reading of the Book of Revelation. And I’m trying to understand my own tradition’s understanding of that book as a description of the end, not of the whole world, but of a specific, oppressive empire. I’m also trying to understand the way climate change, biodiversity loss, and mass extinctions can be understood apocalyptically. And I’m wondering what apocalyptic imagination means in an era when white conservative Christianity has made an alliance with oppressive, authoritarian politics.

I like the tension between the title and subtitle. While the subtitle gestures toward evangelical Christianity’s vision of apocalypse, the title references a song that we sang a lot in the mainline Protestant church. The way that line, “world without end” rebuts the idea of the world ending, from within the Christian tradition that raised me--that was really moving to me.

B: There's a line that struck me: “It's impossible for me to imagine longing for another world.” And I think that as someone in the South, in particular, that is a potentially surprising statement, because the South is a place that is depicted as broken and tainted and filled with environmental problems.

MP: In that essay, I was driving around Memphis with my husband and it was such a beautiful day. I was thinking about the way that some evangelical Christians will talk about this world being a “shadow world” of some greater world to come. And I really struggled to understand longing for this world to end. I didn’t understand why you would put this idea of another world up on a pedestal, when there’s so much beauty here?

I believe that this world is the only one we've got. And that compels me to love it and want to take care of it and repair damage. It doesn't make me long for another world. It makes me long for this world in health and wholeness.

But in that essay, immediately after that line about not understanding longing for another world, I talk about scrolling on the internet and finding story after story about, like, environmental degradation and extinction and people having to flee their homes because of climate change. And I do have this sense of panic—a wishing—for this world to be better than it is. Especially when I think about my kids. I want them to have a different world. Still, my impulse is to put some distance between myself and that idea of longing for another world.

BU: In that last question, I mentioned the South in particular. Given your subject matter, you could have chosen to write about nature only in Memphis, or nature anywhere across the country, or even the world. But you chose to look at places across the South. Can you talk about why?

MP: I only realized late in the game how much of writing this book has been a process of accepting my limitations. I have been working on these essays for about 10 years, but I didn’t really figure out what I was doing until 2020, which is also when I had my son. I have two small kids now. I just—I can't travel that much.

But I’m also just really interested in the South. Like, I read about other places, I care about other places. But I don't think I have anything to say about them. Or I'm not the one to say it. This is where I'm from, and I don't plan to live anywhere else, and I feel very, like, of this place. So writing about the South was what I could do, what I felt capable of doing—physically, as far as I could extend myself, but also as far as I could extend my heart and imagination—there’s more than enough here, in this region, to explore all the questions I felt drawn toward.

BU: In your essay ‘The Terminal Sea’ you start to answer what is a big question behind this magazine, something I ask everyone in these interviews: Is there a ‘Southern thing’ when it comes to nature? Do you have an answer?

MP: ‘The Terminal Sea’ is about a series of landscape paintings that try to recreate the South in the late 18th century, before widespread colonization and industrialization. And that kind of depiction is always going to feel … bereft to me. It just feels narratively incomplete.

I’m not sure that the South is actually any different from anywhere else in the United States. But I don't think you can present nature here without including the textures of human history, of exploitation and extraction. Maybe there are other places where we can trick ourselves into thinking we can just see nature and not have to include that part of the story. Where we think we can leave ourselves out.

So I guess to me the answer is that—again, probably like any place in the United States—human history is woven into this place.

BU: Reading this book raised for me a different answer, one I had never considered. You are bringing in this Christian influence. I grew up attending a Quaker Meeting [in Connecticut], but from a pretty early age, I knew I wasn’t Christian. As an adult, I still occasionally go to Quaker Meeting, but Christianity as a set of beliefs has never had a deep hold in my life. So I'd be curious, from your point of view: I’m someone who’s trying to understand nature the South. Am I maybe blind to anything by not being more conversant in Christian traditions?

MP: I don’t know. I feel like I was writing this book as a way to get better educated myself. Because I came from a very particular sliver [of Christianity], having a progressive, mainline Protestant dad as a pastor. That isn’t what Christianity looks like for most people—at least not anymore. So I was trying to understand white Christianity in the South from a vantage point that I realized was very, very particular.

I felt underread, because I kind of inherited my dad’s faith. I was trying to parse out—what am I getting straight from my dad? What am I getting, culturally, from a different version of Christianity? And, like, how is that form of Christianity influencing the Church at large, and Southerners culturally and politically especially? I was trying to wrap my head around these different versions of Christianity and how they offer different stories to us.

BU: The most marked-up essay in my book is ‘Natural Ends,’ because I feel like it really addresses this question. You’re looking at a really concrete example of different relationship to nature in the South—the practice of natural burial, where bodies are buried with as little environmental impact as possible And you posit that its prevalence in the South is connected to the prevalence of Christianity here.

One of the questions that you ask at the outset of that essay is whether natural burial can be an entry point for Southerners that might be otherwise reluctant to engage with environmental activism or concern. Where did you land on that?

MP: In a sermon at an evangelical church that conducts natural burials, one of the reasons they gave for having their cemetery was environmental stewardship. But then they would say, ‘But we're not environmentalists, we’re not doing anything green’—because they didn’t think environmentalists were, or maybe could be, Christian.

I guess it made me wonder, do people have to get into natural burial because they care about conservation, or is it okay for this church to be doing an important conservation project for totally different reasons? There’s a lot of research that actions can shape beliefs just as much or more than beliefs shape action. So maybe people can maybe come around to new beliefs about the environment by taking environmental action, even if they're not coming from a place where they're motivated by caring for the environment in the first place.

I feel like there's some binary thinking coming from people engaged in conservation or environmentalism that mirrors the binary thinking that I tend to associate with white conservative Christianity. There's a suspicion of people who are coming at it with a different agenda or set of beliefs than conservationists think they should. There’s a tricky gap there, one that can be really fruitful to cross. In the end, I think the actions might outweigh the beliefs. I'm glad that these churches are doing what they’re doing instead of something else.

BU: This is a rare book where you've made your own cover art. You're recognized for both your art and your writing, and your art is sprinkled throughout the book. Does it add something as a practitioner to be able to move back and forth between those forms?

MP: It does for me. It was a really integral part of the process, in the end, because I had written these essays over a long period of time. And when I added illustrations, it felt like I was able to draw them all together, make them cohere in a way that they hadn’t yet in mind. And so it was a way for me to actually see the book as a book, rather than a collection of essays.

What I always wanted was just to make something that cohered, you know. That's what making the art felt like for me, and kind of cinching them all together. And right now, when I'm reading, I'm reading picture books to my kids, and I just love having art in books. All books should have more art. It's like breathing room. And it’s different than language. Art allows something of the of the artist’s mind to transmit really directly to you.

Love everything about this. Grateful for this dialogue btwn two southern writers I hella enjoy + respect 💚