A country [mag] can survive

Two Southern country stars have revived a legendary outdoors magazine. What does it say about our ideas of nature and the South?

[Ed. note: Based on some feedback, I want to underline one point here: I have a ton of respect for hunters and anglers—my critiques of the history of the sport are not meant as criticisms of contemporary hunters. I’ve lightly edited this essay to clarify that.]

It’s rough times for journalism: Condé Nast folded Pitchfork into GQ. The L.A. Times laid off a fifth of its newsroom. Sports Illustrated is collapsing. I could go on, but I don’t want to—it stings. Amid the carnage, though, there is one bright point. One strange bright point: in late January, Field & Stream—the most august of American outdoors magazines—announced that, for the first time in more than three years, a print edition was under production. And that revival was thanks to the magazine’s unorthodox new owners: two top-selling country stars.

One of said stars, Morgan Wallen, posted the following on Facebook:

There’s nothin’ I love more than being with friends around a campfire, on a boat or in a deer stand — and Field & Stream represents all of those to me. Being part of its future is incredible and we want to keep bringing people together outdoors, makin’ memories, for generations to come.

I find this a fascinating document. Wallen’s country bona fides are solid—perhaps problematically so, as we’ll get to later—but these affected (and inconsistent) dropped g’s read to me like the product of a mediocre PR intern. He’s so overtly trying.

I doubt that the idea for this new venture originated with Wallen, or with his friend and co-owner Eric Chruch. What strikes me as more likely is that someone saw these two as fitting figureheads for burnishing this old brand. It’s a natural enough choice, really, but I could not help but wonder: how did we get to the place where country stars are suitable avatars for the outdoors?

Of course, F&S is not focused on rock climbing or hiking or backpacking. This magazine covers a very particular sliver of outdoor activities: the so-called “hook and bullet” sports. Which are indeed popular in the South, though we hardly hold a monopoly on these hobbies.

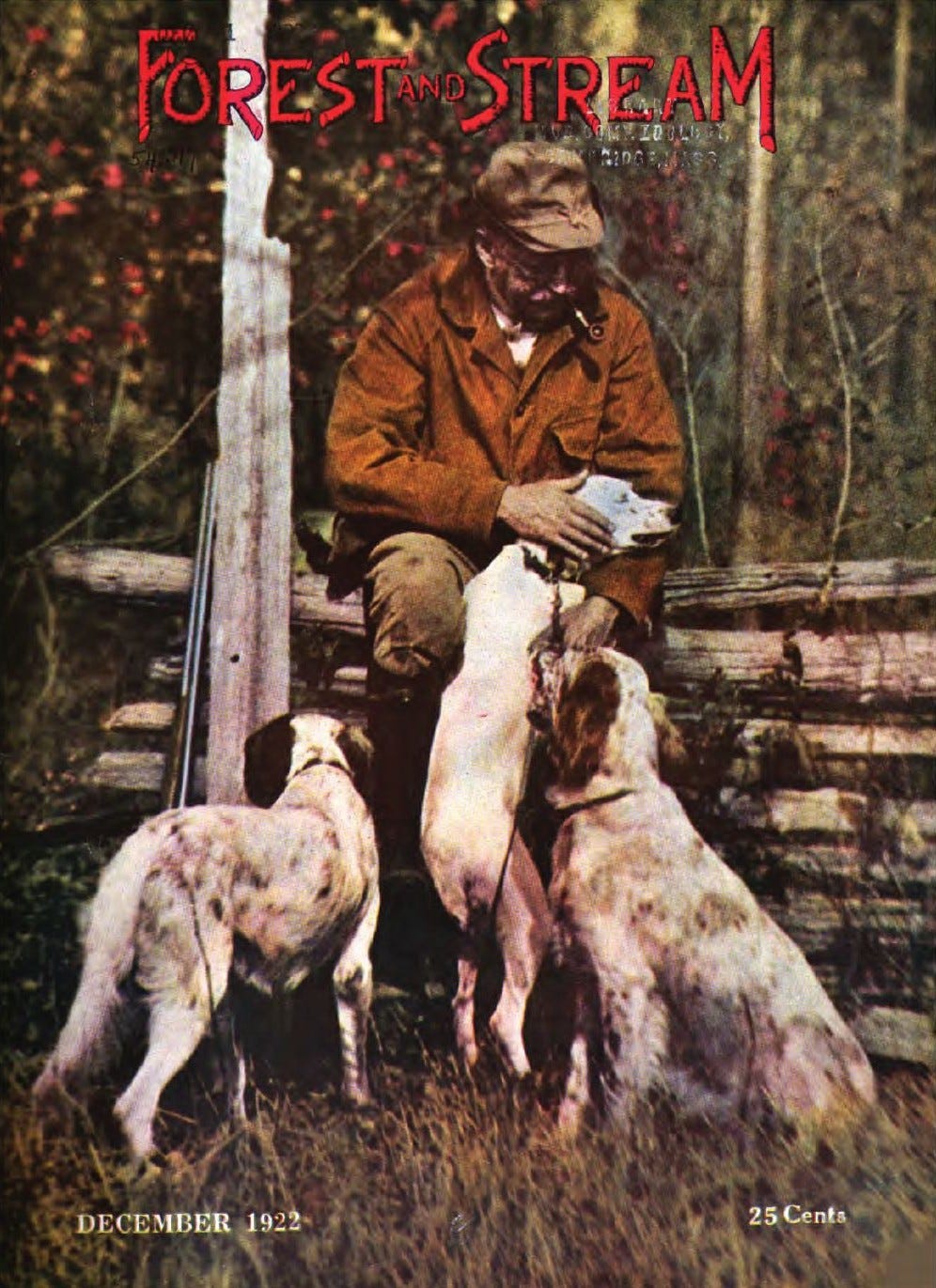

F&S, is, by any honest accounting, a New York publication: that’s where it’s been published since 1898. And thanks to the tangled family trees formed by corporate mergers, you can trace the Yankee lineage back even further. A predecessor called Forest and Stream was first published in New York City in 1873; after a few decades as rivals, the two publications were merged in 1930.

If America’s grand metropolis strikes you as a strange home base for this magazine, that’s because the late nineteenth century was a wholly different era. Back then, hunting was undergoing a reputational shift. Elite Americans had at first considered hunting a habit of the savage and uncivilized; now it was suddenly becoming a sport—a hobby of aristocrats. Teddy Roosevelt—who wrote pieces for both F&S magazines—was, despite his buckskin jackets and backwoods exploits, a NYC boy. The iconography of the outdoors lodge that we know today—think the grand gabled entryway into a Bass Pro Shop—is mostly drawn from the style of these aristocrats’ upstate lodges in the Adirondacks.

Let me be clear here: hunters and anglers are among the greatest advocates for conservation we’ve got. They know, intimately, why intact landscapes are so important. And this has been the case since the beginning. The leaders of this burgeoning sport-hunting movement pushed for the expansion of public lands. Today, around 6% of Americans are hunters, according to one survey. The land would be better off if that number were higher.

But if we want to increase those numbers, we can’t squint past some of the uglier roots of this movement. These city men believed that a crisis was at hand: The frontier had rolled so far west that it had consumed itself. Roosevelt worried that with no more wilderness to conquer, Americans would lose the “vigorous manliness” that had set the country’s first generations apart. Hunting, he said, builds the kind of rugged characteristics “without which no race can do its life work well.”

Among its positive contributions, this movement helped inaugurate the first big national parks out West. Down South, though, nearly all the land was already private property. So a different model developed: Wealthy Northern investors moved down, bought up plantations, and turned them into luxury hunting resorts. “Leave the false glare and glitter, the hollow show of a city life,” one writer urged in an 1881 dispatch in Forest and Stream that extolled the virtues of the old aristocratic life down in North Carolina.

Country music has its own tangled past, of course, as you probably know. The short version: the genre emerged as a marketing label meant to distinguish white folk music from the Blacker sounds of the blues. I love country music, even radio-pop country, but these origins can’t help but color how certain lyrics hit.

When I tried to find country songs about hunting, the consensus favorite, according to Reddit, was “A Country Boy Can Survive.” It’s a grim song. From an apocalyptic beginning—

The preacher man says it's the end of time

And the Mississippi River, she's a-goin' dry

The interest is up and the stock market's down

And you only get mugged if you go downtown

—Hank Williams, Jr., crescendoes into a dark climax. A friend of his, a city boy, is stabbed in a mugging. (“For 43 dollars my friend lost his life.”) Ol’ Hank, meanwhile, who has previously extolled his ability to hunt and fish, declares that he’d

love to spit some Beech-Nut in that dude's eyes

And shoot him with my old .45

'Cause a country boy can survive

Vigorous manliness, sure. Aristocratic, not so much.

The first country song to take up hunting, at least that I can find, was Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Shotgun Boogie,” released in 1950. It’s a rather tamer love song.1

It makes sense that country music and hook-and-bullet culture merged in this era. Field & Stream and its rivals had over the prior years decided to broaden their readership, focusing not just on millionaires, but also the growing middle class. The price of guns was dropping, and salesmen—“missionaries,” as they were called—“hawked guns through thousands of country stores, all the while flattering their patrons by calling them ‘sportsmen,’” as historian Daniel Justin Herman wrote in The Magazine of Western History in 2005. By mid-century, Herman notes, a quarter of U.S. men owned hunting licenses.

But this democratization also hurt the sportsman image: The aristocrats could no longer distinguish themselves with the label; so, for at least a portion of the culture, hunting became the kind of thing associated with men like Morgan Wallen (b. N.C.)—and Hank Williams, Jr., too (b. Shreveport, La.)—who tend to drop their g’s. Wallen, you may have heard, got into trouble a few years back for casually dropping the “n-word.” But in the wake of the controversy, sales of his album surged. The old roots of country music are far from dead.

The question I have is whether someone like Wallen is the right figure to expand the bounds of these sports. I should note that I quite like the music of the other star F&S owner, Eric Church, who has managed to sustain a mildly alternative image in the conservative world of country pop. He’s written songs decrying racism; he’s called out the NRA for standing in the way or reasonable gun control. He’s been described as a mentor to Wallen, who says he is working “to learn and try to be better.”

To get your copy of the new print Field & Stream—which will be oversized and 120 pages thick—you have to sign up as a member of the “1871 Club.” That’s a revealing date, in my opinion, given that it’s more than twenty years before Field & Stream was ever published. It’s two years before the birth of even Forest and Stream.

So why 1871? It turns out that that’s the year when the outerwear manufacturer Gordon & Ferguson Merchandising Company first formed. And why do we care about an outerwear manufacturer? Nearly half a century later, in 1915, the company started selling clothing under the label “Field & Stream.” The magazine had never bothered to trademark that name, which by the 1980s led to legal fights. They were eventually settled in a managed detente; the two brands, with one shared name, parceled out different bits and pieces of the outdoor gear market. The magazine got binoculars. The clothier got jackets. Etc.

Thanks to the magazine and the clothing both, F&S has become a recognized and venerable name—which has lured several hungry brands throughout the year. Dick’s Sporting Goods bought the licensing rights to the F&S name in 2012, and the next year launched its first Field & Stream store—meant as a rival to Cabela’s and Bass Pro Shops. By 2021, though, they’d begun to pivot: the original Field & Stream store was relaunched as “Public Lands”—a climbing-centric, athleisure-style store. There was at time, I’d note, a rash of articles lamenting that the number of U.S. hunters was in precipitous decline.

Still, others began to eye the old brand. Early last year, a pair of developers announced that they were launching Field & Stream Lodge Co.—a chain of hotels in “gateway” communities famed for their outdoor recreation but lacking anything in the mid-tier price range. I’m not sure if those plans have changed thanks to the new magazine, which is less a rebrand than a Frankenstein monster: the deal stitches together, for the first time, the publication brand and the apparel and retail name. The newly conjoined F&S will soon launch a “limited-edition apparel collection” and, fittingly, given the new owners, a “Field & Stream Music Festival.”

I’m guessing the mastermind behind this portfolio is not the musicians, but the third buyer, the newly installed president of this era of Field & Stream, a Texas-based businessman named Doug McNamee. He’s got suitable credentials, as the former president of a company called Magnolia, first founded by HGTV stars Chip and Joanna Gaines. From a small retail store in Waco, Texas, the company grew to encompass, according to McNamee’s LinkedIn page, a “national home and lifestyle brand spanning retail, food, hospitality, a quarterly lifestyle magazine, New York Times bestselling books, design, construction, real estate and a forthcoming linear television network, among other ventures.” This appears to be the template for the new F&S: take a familiar brand and sell sell sell.

One of the developers of the F&S lodging concept last year told an industry publication that “the idea of getting out of the metaverse and into the universe is powerful.” But the new F&S feels to me like one more metaverse—a carefully constructed hologram, stitched together from little virtual threads plucked from the messy snarl of corporate history.

None of this is meant as a criticism of the magazine. This is how modern journalism works, for good or bad. If Southlands ever makes real money, it will be because of a similar, if smaller expansion. (A Southlands-branded collection of glamping campgrounds, anyone? Investors, if you’re interested, you’ve got my email address right here.) Really, I find the relaunch of F&S heartening. Not because it’s one more print magazine, though that’s great. It’s more because it may signal a shift in America’s views of hooks and bullets.

While I don’t fall for the line that every hunter is automatically a conservationist, I do think nature in this country would be doing better if more people took up this sport. (I am hoping to learn to hunt myself.) Anecdotal reports suggest that the Covid lockdown spurred many people to get back outside. “What a whirlwind,” one Michigan wildlife official told writer Malia Wollan when she asked about the boom in sales of hunting licenses. Wollan’s profile depicts Steven Rinella—who helms his own hunting media empire, known as “MeatEater”—as an “environmentalist with a gun,” a potential bridge for our divided times. The new F&S strikes me as another olive branch—a way to expand the image of hunting, if just slightly.

There is further to go, of course. I wish that the hard line between the hook-and-bullet sports and the rest of outdoor culture—the line that separates F&S from Outside, say—might begin to dissolve. Wouldn’t be nice if hunters and backpackers lobbied together to protect the nature we love? To get there, though, hunting may have to reach beyond the bounds of country music.

There are of course earlier folk songs that take up hunting.

Interesting perspective and update. I've never read F&S, it isn't exactly my genre--I was definitely more of the Outside and Backpacker person when I read them, though my husband has read his share of niche fishing magazines over the years. The whole summary linking F&S's business ventures to a similarity to Bass Pro and Cabela's was apropos was I was just at BP yesterday. I like going in that store, it's interesting but as a non-hunter I have no idea what the cost of bullets are. And we were behind a couple who bought maybe 3 or 4 boxes of ammo yesterday and spent over $1,000. How is that even affordable to most people, especially if there would be a push to have more people hunting? Which made me wonder a: how much debt people go into for gun culture and b: what the average income is for hunters and gun owners (and the fanatical ones).

If you want to talk about merging of hunting with nature, you should check out the Native Habitat Project Instagram and there's a FB group called Native Habitat managers. The latter often talks about native habitats and property management with regard towards hunting and Kyle at NHP on IG is also a hunter and does skew towards that but with a big conservation minded outward appearance. It's probably the closest we have towards that merging right now.

Boyce, I'm a big fan so I feel the need to weigh in here because I work in conservation here in Louisiana and some of our most outspoken citizen conservationists are hook and bullet outdoorsmen and women. Ducks Unlimited, Vanishing Paradise, CCA to name the very least I could think of spend millions in conservation aimed at wildlife biodiversity every year because they understand better than most what it means if the health of our land is compromised. And sure, not every hunter is thoughtful, but not everyone working in conservation is thoughtful either. I can point you to countless speaking engagements, articles written, TV episodes, public comments written, podcast episodes, etc all undertaken by hunters who care about this land so much that they put in their own time to support conservation all across the delta. I hope you'll reconsider the way you portray the hunting/angler community in the future because I have to say, we're working our butts off to maintain great relationships in this area and we owe a great deal in Louisiana especially to hunters and fishermen who've made it their life's work to speak out in favor of conservation.