Field Guide: American Chestnut

Has an Appalachian icon—and its (in)famous genetic rescue effort—gasped its last breath?

“Your kind never sees us whole. . . . If your mind were only a slightly greener thing, we’d drown you in meaning.”

—Richard Powers, The Overstory

The tale of the American chestnut, told in brief, reads like the logline for an Oscar-bait movie.

An American hero, laid low by disease.

A quest—brave and groundbreaking, contentious and potentially revolutionary—to save the hero.

For decades, scientists have been trying to engineer a transgenic chestnut tree, one that could survive in our modern, pestilential world. Last year, the final denouement looked close: the tree was working; the federal government seemed all but guaranteed to give a seal of approval. So the chestnut would blossom once more.

Then, in December, an unexpected twist: Sloppy science. Jilted funders. This is not where the movie version would have gone…

If trees, as writer Richard Powers claims, can drown us in meaning, what is the lesson here?

Powers’ Pulitzer-winning novel The Overstory, a rare novel about trees, begins, appropriately, in “the time of chestnuts.” Back in the nineteenth century, the nuts would rain down every fall from Maine to Georgia—“yet one more windfall in a country that takes even its scraps right from God’s table,” Powers writes. People would gather, collect, and celebrate.

The American chestnut was beloved—the one tree that Americans may have come close to seeing whole.

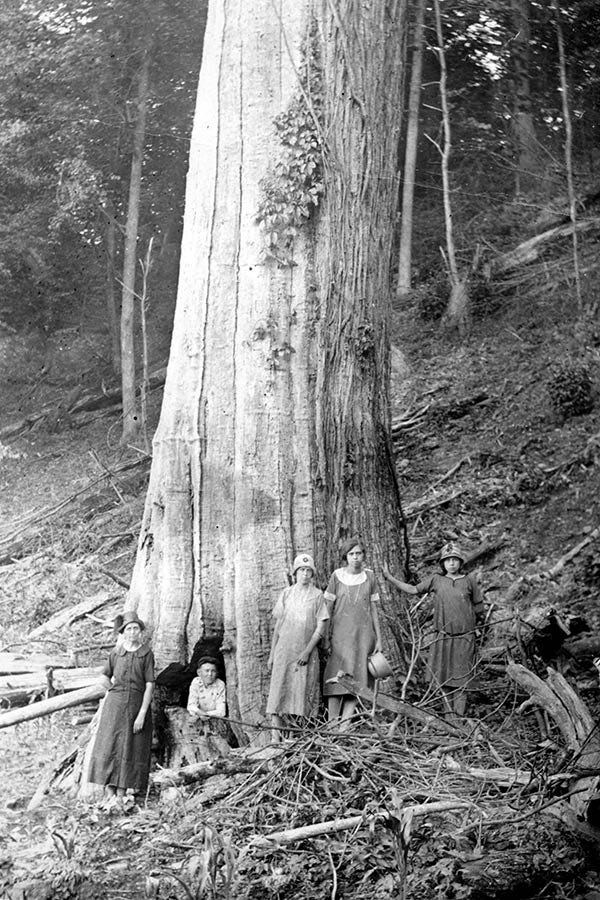

The chestnut trees were hard to miss, given that the largest rose to 130 feet, straight and perfect—the tallest trees in the eastern forests. When their leaves turned yellow, they’d brighten entire mountainsides; in springtime, their burst of pollen came like a second snow. The wood was straight and strong. It refused to rot or warp. Fencing, furniture, coffins, homes: these were all built from chestnut wood, which at the turn of the century constituted a quarter of the nation’s timber. Chestnut tannins were used to treat leather. The nuts themselves fattened hogs. A “perfect tree,” it’s sometimes called.

Life in Appalachia—life in rural hollers, especially—depended on this tree and its many gifts.

Then came the fungus.

First in the Bronx, in 1904, where it must have arrived as a stowaway. Blame a love of beauty: someone wanted to ornament their garden with an Asian chestnut. And with it came an Asian fungus.

It’s a classic story of epidemiology: The trees in Asia, long exposed to the blight, had developed resistance. American trees had not. The blight sneaks through the bark, girdling the trunk, starving the tree. Year by year, the disease spread, crossing the Mason-Dixon line around 1920. By 1950, the blight had conquered the chestnut, expanding across the whole of its range.

Once, we had five billion chestnut trees. More than 90% perished throughout the twentieth century—what one biologist calls “the greatest ecological disaster in North America since the ice age.” For many in Appalachia, the disaster was more than ecological. Without the wood, without the nuts, farmers had to choose: “Go into the coal mines, or move away,” as Gabe Popkin put it in the New York Times Magazine in 2020.

The tree itself did not move away, though. The survivors still amount to more than 400 million specimens, though theirs is too often a strange, sad fate. The blight attacks, and then the tree becomes a stunted spindling—15 feet tall at best, perhaps an inch wide.

It is, as Katherine Wu recently put it in The Atlantic, “an endless cycle of adolescence, death, and rebirth.” How sad is that? To emerge, again and again, into a world that wants to kill you.

Efforts to save the tree began almost immediately after the blight arrived on our shores. First the U.S. Department of Agriculture dispatched a “plant explorer” to China to search for a replacement. The best candidates all proved too small to compete in American forests. Through the 1940s, the USDA bred the surviving chestnuts, without much luck. In the 1950s, besot by nuclear science, researchers bombarded chestnuts with radiation, hoping to create a lucky mutant.

Founded in the 1980s, the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) eventually became the leader in this long quest. Their initial strategy was to “backcross” chestnut trees with their Asian relatives, creating a tree that was mostly American, but that has enough resistance to survive. Progress has been slow.

There’s been a parallel effort—far sexier, though also more controversial: scientists were trying to engineer a GMO chestnut. In 2015, TACF decided to throw its money and reputation behind the project.

The resulting tree—dubbed Darling 58—has a gene, drawn from wheat, that produces an enzyme that breaks down the fungal pathogen. Otherwise, it’s identical to any other American chestnut. The hope was that, once planted sufficiently, this gene would spread into other, wild-growing chestnut trees.

TACF’s funding was big news—a sea change. Here was an environmental group supporting GMOs. The idea still sparked uproar, particularly among Indigenous groups, but genetic engineering, once a kind of bogeyman, had settled into a new reputation, supported by many conservationists.

By 2019, the research team creating the trees, at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF), was confident enough in its performance to file a petition with the USDA. They were seeking deregulation: It’s ready, they were saying, in essence: It’s time to set this tree free.

I had been reading bits and pieces of this history for years when, last spring, I started reporting on a different effort to plant GMO trees. As I wrapped up my reporting in June, I figured I ought to check in on the famous chestnut. The petition was sitting there with the USDA, still undergoing review. It had to be coming any day, I figured.

So the latest twist came to me as a surprise: in December, TACF suddenly withdrew its support of the transgenic tree. They had no fear that trees were dangerous to forests—they were not a “pest risk,” as it’s put in the industry. The problem was more that these trees just did not seem to work.1

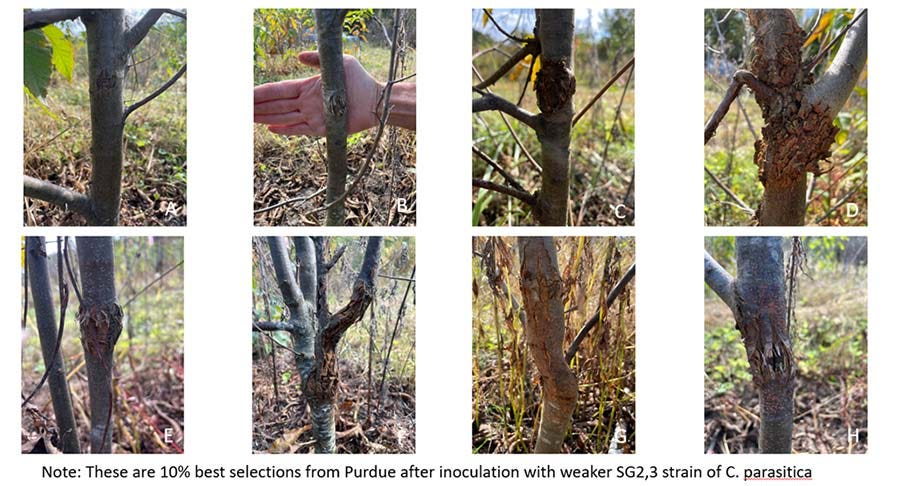

In tests conducted around the country, the new chestnuts grew short and stubby. They had brown leaves. They were quick to die. One potential cause was that the trees were constantly expending energy making the magic enzyme, which reduced the energy they could devote to growth.

But TACF stumbled on another major issue: The SUNY researchers made what they called an “unfortunate labeling error.” When they created Darling 58, they made other chestnut variants, too, with the wheat gene inserted in different places in the genmoe. It turned out that the trees sent out for field tests were actually a cousin—Darling 54. Which was a problem, since, as TACF noted, the Darling 58 tree population was now at most “a handful, and perhaps even only one.”

It’s worth noting that the tree had already become controversial within TACF; some prominent leaders had resigned over their opposition to transgenic technology. Philosophical differences had emerged between the foundation and the scientists: SUNY-ESF was contemplating for-profit models to distribute the tree. TACF was a committed nonprofit.

Then there was the fact that ESF never notified TACF about the mixup—they only heard about it from other researchers. The foundation, in announcing its withdrawal of support, noted that the pile-up of mistakes threatened to erode public support for future conservation efforts that employ biotechnology. And they have hopes that a new transgenic chestnut might work better—by only producing the enzyme when it’s needed.

SUNY-ESF, for its part, has announced its intentions to keep on pushing for deregulation of its Darlings.

The writer Sabrina Imbler recently took up the topic of de-extinction—“a word that overpromises,” as they put it.2

We can’t ever revive long-lost species like mammoths and dodos. The best we can make are proxies, their genes mixed with those of their closest living relatives—and we won’t know how close they are to the real thing. Besides, Imbler says, how sad would it be to be the first of your kind to return? How lonely to be the one and only—no one to teach or guide you?

De-extinction, they concludes, is “a grand gesture,” but not much more. Even if it works, “it will not change the path of shortsighted greed that got us here.” Other species are still dying too fast.3

The American chestnut is not extinct—remember that those sad trees, child zombies, keep endlessly reappearing—but the trangenic tree project, too, strikes me as a potentially too gestural. “The hope is that you can fix something that we as humans broke,” a representative of the American Chestnut Foundation recently told The Atlantic.

We want to save the hero—the great, lost tree.

Consider how we broke the chestnut tree: This is not the case with the bison, hunted to the brink of extinction. This is not the ivory-billed woodpecker, stripped of its home by loggers. How guilty do we need to feel about the American chestnut? We have crosses to bear, mistakes to rectify. And there are reasons to save the chestnut. But we’re letting ourselves off too easy if we conclude these are all one and the same.

“The heart of coal country,” Gabe Popkin wrote in the New York Times Magazine in 2020, “happens to overlap the heart of what was once chestnut country.” And, here, I think, it is worth feeling guilt: some of these Appalachian chestnut forests were razed so coal could be ripped from the ground.

Now, some of these forests have been replanted—a powerful symbol, I admit, but one that strikes me as rather grave-like.4 Those new forests will still mark a loss, because restoring a lost American tree will not restore lost American cultures. Its not just backwoods holler culture, either. Popkin notes, for example, that some Indigenous groups have completely lost the traditions associated with the chestnut tree. At the same time the trees were dying, Native people were being forced into boarding schools, where forced assimilation was the rule.

There is one last plot twist in this story—a fact I feel bad sharing so late in this essay, but it’s a fact so infrequently included in the epic tale of the chestnut that I myself learned it belatedly: Down here in the South, our trees were dying before the blight ever arrived. A different fungus arrived on our shores almost a hundred years earlier, spreading “root rot.” This microbe can’t survive cold winters—but since climate change can also be thought of as Southern weather spreading north, root rot will become a problem for any chestnuts that we manage to revive. In the hundred years since the end of the time of the chestnut, the world has changed.

Richard Powers challenged us to hear the meaning of trees. The lessons I see in the chestnut are the same notes I hit again and again in these newsletters: the need for humility; how little we know of how carefully wrought this world is, how precious, how fragile. How dynamic: what we know and love can be so easily gone.

How no tree stands alone, unlinked to the rest of what we do.

Hunting for chestnuts

Despite the blight, despite the root rot, there are some blight-free survivors across the South, though sometimes their locations are held as secrets.

To help in your search, the American Chestnut Foundation offers a field guide of its own. Head to the woods of the Appalachian Mountains or their foothills, they say. The survivings tend to live “in acidic soils on dry, well-drained hillsides (facing south and east, where the sun is hotter and the soil drier). Also look on sandy soils that have good drainage.”

The southernmost known stand of chestnuts was found in 2006 near Warm Springs, Georgia— “along a hiking trail not far from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Little White House at Warm Springs,” in case you want to try searching there.

Substack is warning me that I’ve blathered on long enough that I may be straining the edges of your inbox with this email. So I’m going to send out this week’s news roundup in a separate email on Thursday!

This was the same fear that ecologists shared with me about an effort to create a fast-growing tree for the sake of carbon removal. Trees as complex beings, hard to re-engineer.

[Ed. note: In my initial version of this newsletter, I misgendered Imbler. My sincere apologies!]

They also notes that the big win in de-extinction is less ecological than financial: the investors who prove the technology stand to earn a lot of money. Similarly, in the case of the chestnut tree, some critics worry that corporations like Monsanto are quiet supporters, hoping that approval of a conservation-oriented GMO plant will boost the technology’s reputation, and pave the way for other approvals.

The replanted trees are crossbred, not genetically engineered. The idea, as Popkin writes, is that “they could become the parents of a new generation of trees that will someday rival the forest giants of old.”

This is a comprehensive, beautiful, and sobering look at the iconic chestnut tree. Thank you, Southlands.