“The island seems to have a tenacious hold on the human imagination,” the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan wrote in his classic book Topophilia.

This fact, he notes, stands in contrast with their role—or rather lack of a role—in ecology and human evolution. Islands tend not to be places of great species abundance. They played little role in shaping our species’ trajectory.1 To explain this riddle, tuan notes that islands’ apartness seems to offer an escape from everything that is wrong with the world—as if on an island we can become “quarantined by the sea from the ills of the continent.”

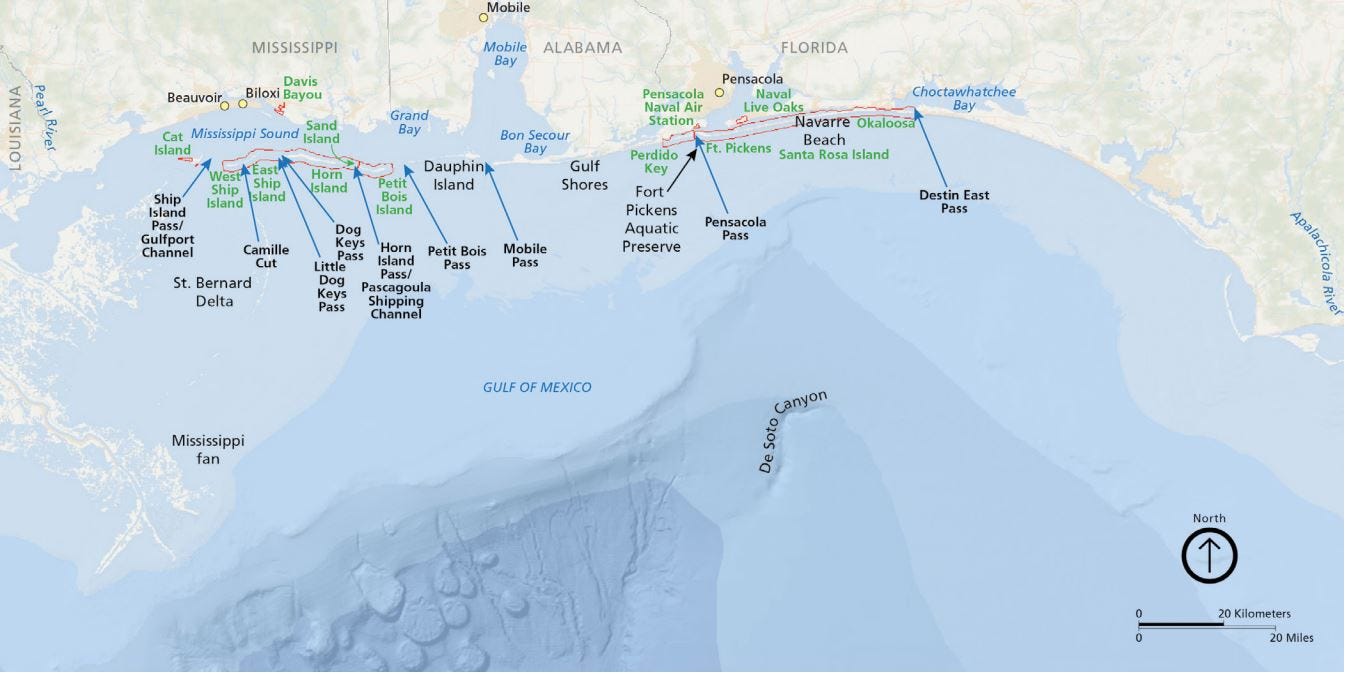

A few weeks back, a friend organized a group excursion to one of my own personal paradises: Horn Island, one of the barrier islands running along the edge of Mississippi’s coast. I first discovered Horn Island years ago, when I wrote a profile of the artist Walter Anderson, who rowed five miles across the Mississippi Sound so he could sit in the sand and paint in watercolor one of the most beautiful expanses of the South.

One signal of how special this place is is the fact that almost none of Mississippi’s land has been deemed worthy of being named a national part; the only state that is more bereft in Kansas.2 But Horn Island is part of a national park—and is an official wilderness, at that.

Barrier islands are not a solely Southern thing, since they extend north to New England. But there are no true barrier islands on the Pacific, so our coastline constitutes the vast majority of the U.S. supply. (Indeed, Florida’s barrier islands make up a third of the full length of the country’s barrier islands;3 Padre Island, in Texas, is the largest barrier island, spanning more than 100 miles.) Barrier islands are typically part of a twinned ecosystem: across the sound, on the mainland shore, you’ll find a marshy estuary. That means that the sand that’s collected on the island has even more appeal, since it’s the closest thing to a beach around.

We’ve all got different ideas of what constitutes a paradise. For some people, I suppose, you need to travel for hours away from anything that seems civilized. From Horn Island it’s easy to see the lights back on land. Still, as if to prove that five miles should be considered sufficient, on the first day of our adventure, the winds were too strong for our borrowed boat to reach Horn Island. We had to camp instead on Deer Island—which is not a barrier island at all, but a piece of the former mainland that has become separated.

Some of our group groused about this stopover, since Deer Island is indisputably not Horn Island. I was happy enough to scout the place, though. It once housed an amusement park, and if left unprotected, surely some foolhardy corporation would choose to plant a casino out there—but it’s owned by the state, and will remain undeveloped. And it’s close enough to shore that you can easily reach it in a small paddle craft. So my verdict is, if that’s your best option, it’s a good choice for a night or two of camping. An island is an island, after all.4 But if you can get someone to haul you out to Horn Island and back, that’s your best choice.5

Horn Island is not so big that you’ll ever forget you’re out there, separated by the water, but it’s big enough to include beaches and forests and wetlands and sandy expanses that feel like deserts—what can feel like a tour of an entire continent in the span of a few miles.

Barrier islands are constantly changing—reshaped by winds, tides, and waves. That makes it hard to know how old Horn is. Analysis of buried beach ridges suggests it’s less than 4,500 years old. Already it’s disappearing, thanks to the battering effect of climate-driven storms and the diminishing supply of sediment pouring off the continent. Here, too, is a way they resemble paradise: They are only ever a fleeting thing.

The roundup

Garden & Gun launched an exciting new podcast today, well aligned with Southlands: The Wild South features conversations with legends of the sporting world.

The Seven Rivers Canoe Club offers a useful report from Buckatunna Creek—part of the Southlands-approved Pascagoula watershed.

Finally, Axios offers a look at the “extraordinarily busy” hurricane season we need to expect this year.

Southern environmental jobs

Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana: Native plants program coordinator; oyster shell recycling program coordinator; social media manager

Atchafalaya Baykeeper: staff attorney

Though they can lead to diversity: quarantined on an island, populations quickly diverge genetically from their mainland relatives, producing new subspecies. The undersized Key deer of Florida are a prime example.

Mississippi does, of course, have many national battlefields, which are overseen by the National Park Service; but these have little to do with landscapes or beauty.

As of 2000, 1.4 million people lived on U.S. barrier islands, half in Florida. I don’t recommend this choice.

Sometimes just riding a ferry across the Mississippi River, to the quiet neighborhood across from the French Quarter, is enough for me to get the island effect, even.

Many thanks to Matthew Mayfield for the rides; if you find yourself on Mississippi’s coast, go visit his restaurant, Tay’s BBQ—at the very least seek out his smoked tuna dip—or pick up some of his oysters.