Field Guide: Combahee River

A new Charleston exhibition showcases a different kind of outdoors hero

I get a lot of emails from PR reps, and usually I delete them on sight. But if you put the word “river” in the subject line, I just might perk up. It’s one such email that alerted me to a new exhibition at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston about the Combahee River Raid.

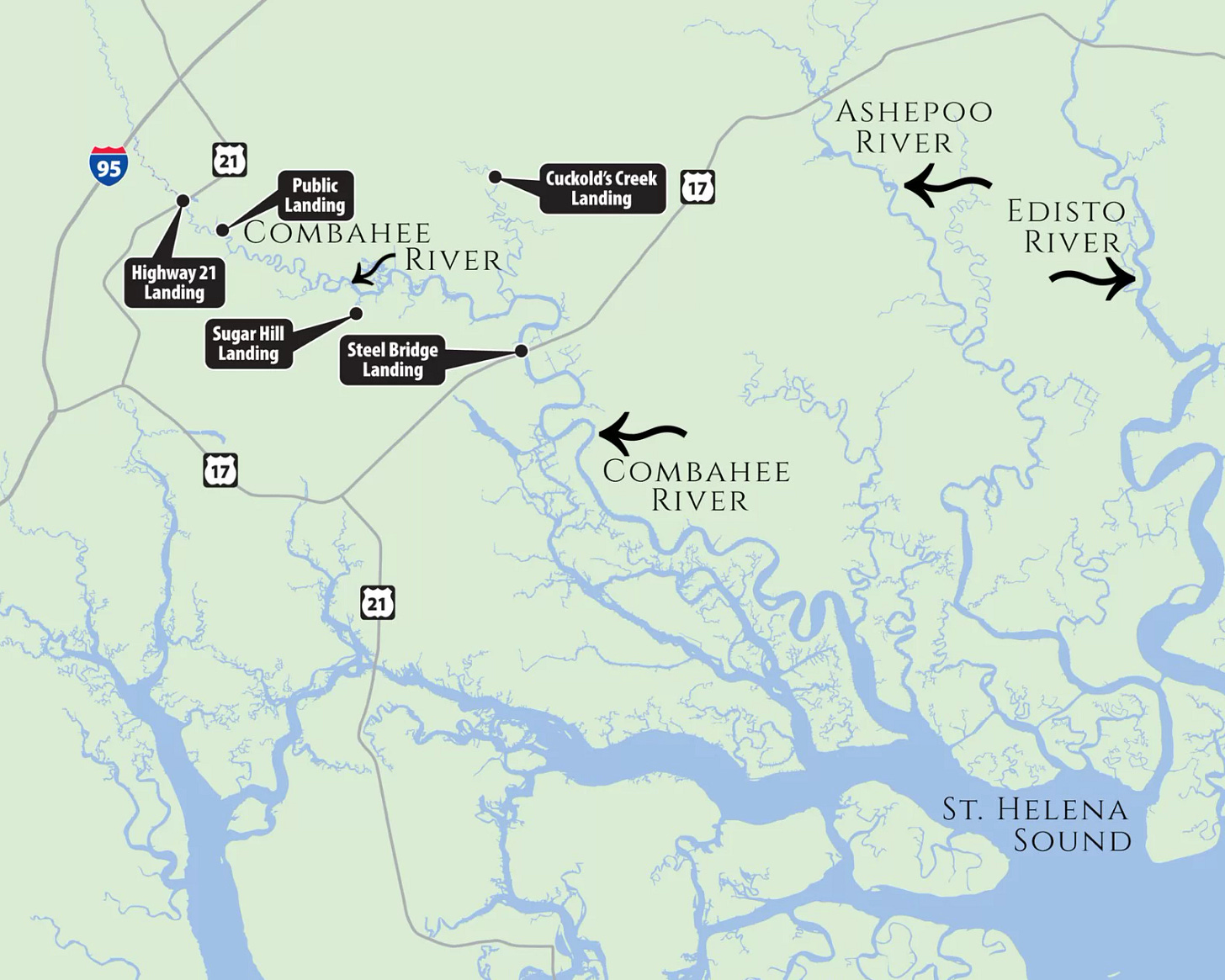

Before we get to that raid, let’s back up to talk about the Combahee—pronounced COME-bee—itself, and about the other two rivers, too, the Ashepoo and the Edisto, that make up the ACE Basin. It’s a bland acronym, but a spectacular region, sometimes described as the last wild place on the Eastern seaboard. Here, just southeast of Charleston, you can chase deer and ducks and crab and shrimp and bream. You can paddle or hike. Or, as the New York Times once noted, you can just drive the roads: “The region is so sparsely populated that even from the pavement, you experience prime wildlife habitats with all five senses.”

There’s a good story here. This was once rice country, home to sprawling plantations, but few survived the Civil War. When development began to swallow the surrounding coastline in the 1970s and ‘80s, a coalition arose to preserve this paradise. There is good public land here, but private land has been the true key to local conservation; more than 275 conservation easements have been signed here since 1989.

That means, though, that the characters in this story are of a certain ilk: rich white men, mostly, who are turning their grand plantations into nature preserves.1 And lord knows I love a good ol’ boy sportsman—y’all will be key to the success of Southlands, friends—but I’ve always been interested in other outdoor heroes, too.

Which leads me back to that art exhibition. I don’t have space here for a full account of the Cumbahee River Raid; if you’re interested in that, turn to Combee, by Edda Fields-Black, which just won a Pulitzer Prize, and on which the exhibition is based. The short version is that in 1863, after proving her mettle on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman led a raid into the Lowcountry to free more than 750 enslaved field workers. Tubman was the first woman to lead a U.S. military operation.

For the same reason the ACE Basin allures outdoors enthusiasts today, its landscape demanded extraordinary courage then. The exhibition includes landscape photography that "shine[s] a light on how dangerous it was for the enslaved laborers to flee during the raid, through deadly tidal rice swamps with snakes and alligators," notes Angela Mack, former president and CEO of the Gibbes Museum.

As part of her research, to understand what the operation truly entailed, Fields-Black walked the terrain herself in the middle of the night under moonlight. How many of us would dare attempt that journey? Consider it a reminder of the countless untold stories our Southern landscapes hold—and the heroes who moved through them long before our conservation victories made headlines.

—Boyce

Picturing Freedom: Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Raid is now on exhibition at the Gibbes Museum of Art, and will be open through October 5.

The Lowdown

Here comes another busy hurricane season—alongside a DOGE-ravaged National Weather Service. // A historic lighthouse has been restored at Dry Tortugas N.P. // Georgia shrimpers are struggling. // Can farming save Louisiana’s storm-ravaged oysters? // Maybe Louisiana will get a smaller diversion. // When it comes to a mining decision, Okefenokee still waits. // Love ‘em or hate ‘em, iguanas have arrived in Key West.

Ted Turner helped lead the way in 1989 by placing easements on a 350-acre plantation he owned in the region.

Wow, the GA coast has a strikingly similar story

I was so excited to read this as we are in Charleston right now but I see it’s not opening until October.