When I hear the word “peat,” I usually think of Ireland, perhaps because of a family trip a few years back. To heat an Irish house by burning harvested peat is a timeless tradition—and, as of last year, illegal, thanks to concerns over climate change.

That law is a sign of how important this strange slime is.

“Peat is not a simple substance,” as Annie Proulx puts it in her recent book, Fen, Bog & Swamp. Indeed, there is no standard scientific definition. But you can think of it as accumulated muck that is a bit watery and contains a good dose of dead organic material—often still distinguishable as former plants.

According to a 1922 U.S. Geological Survey bulletin—which was mostly focused on how peatlands can be put to commercial use—“the accumulation of this material is governed very largely by topography . . . and by climate.”

In terms of topography, you’re looking for “land surface [that] contains depressions, or flat or gently sloping, poorly drained areas in which water may collect and stand permanently.”

What’s magic about such depressed and poorly drained lands is that the water they retain prevents the bits of plants—the moss and twigs and seeds and trunks and roots that drop to the ground—from decaying. And since plants’ biomass is mostly made from atmospheric carbon, converted via photosynthesis into the building blocks of cells, the undecayed plants serve as a tremendous source of carbon storage. Peat can hold between ten and thirty times more carbon than the plants growing from its surface. Peatland covers just 3% of the Earth’s surface but, according to a widely circulated statistic, contains more than twice the carbon as all of the world’s forests. By some estimates, the world’s peat holds nearly as much carbon as all terrestrial biomass—all the plants and animals living on land.

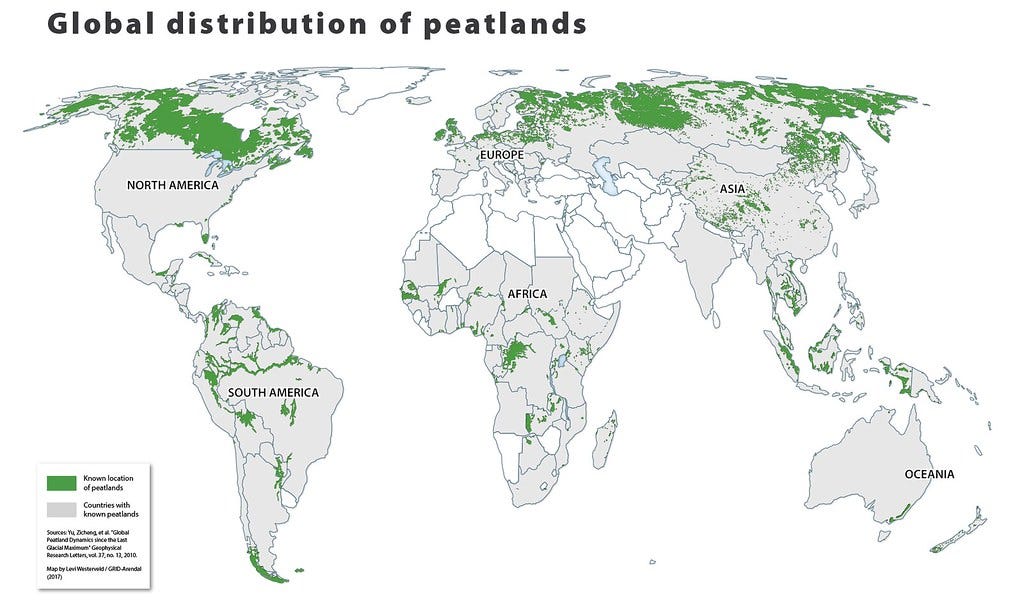

As for climate, this precious muck is mostly found in northern landscapes, where cool temperatures help further inhibit decay. (Thus the Ireland fame.) Further south than “the South,” too, in moist, tropical landscapes, the tremendous rates of plant growth can also help encourage peat formation.

Here in the South, we may be famous for our swamps. But, according to the U.N., only 30% of U.S. wetlands are peatlands.1 And the kind of warm-temperate landscapes that typify the U.S. South contain only 2% of North America’s peatlands.

Despite their rarity, these little slivers of Southern peatlands are tremendously important in our era of climate change. A 2022 study by researchers at Duke University found that rewetting just 250,000 acres of former peatlands—places that were drained for agriculture but are now unused—could prevent 4.3 tonnes of carbon from escaping into the atmosphere. That’s equivalent to 2% of the total emission reductions required for the U.S. to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. Duke has invested in a 10,000-acre carbon “farm” in the pocosins, a kind of peat-forming wetland that features evergreen shrubs, and mostly appears in North Carolina. These are an endangered ecosystem: in the1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, two-thirds of North Carolina’s pocosin landscapes were drained.

The other Southern peatland seen in the headlines lately is Okefenokee Swamp. Its name comes from a Muscogee phrase for “bubbling water,” which is almost certainly a reference to the methane that bubbles up from the deep peat. [UPDATE: it is perhaps more likely that the name means “quivering water.] According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the peat here holds 95 million tons of carbon—“about the same as the net emissions from all Georgia’s homes, businesses and transportation in a year,” as Georgia Public Broadcasting notes. This is the largest undisturbed deposit of peat anywhere on the coastal plains along the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico.

There’s a proposal in place to mine titanium from a ridge alongside the Okefenokee swamps. The mining company says the mining won’t affect the hydrology. Lots of people—including multiple agencies within the federal government—disagree. That ridge, some note, is part of what holds the Okefenokee’s waters in place. So what, we must ask, is that titanium really worth?

May I ask where you found that transliteration of Okefenokee? You say here it is "from a Muscogee phrase for 'bubbling water'" and I have no doubt you have a source, but I have always heard it is from a Choctaw phrase for “The Land of the Trembling Earth,” which is what NPS and other sources have.