Sorry for a delayed newsletter! My wife and I were packing up and heading north for the summer: through mid-August, Southlands will be published from New York City. To make up for a missed week, there will be two essays this week, one today and another Thursday.

Up first, I’m once again featuring an adapted excerpt from my forthcoming book—about which I should have big updates soon! Many thanks to my good friend and longtime collaborator Rory Doyle for allowing me to use some of his photos.

There’s an old legend—a falsity, as far as I can tell—that the “Yazoo” in the name Yazoo River means “river of death.”1 The story makes sense, though, because the Yazoo, which marks the southern edge of the Mississippi Delta, has often been a tough place.

We think of the Delta today as farmland, but for thousands of years this was one of the world’s great forests. Cypress, oaks, tupelo—water-tolerant trees, mostly, because the low land here would be inundated every few years by the rising Mississippi. It’s a rich and fecund place, home to wealthy and powerful chiefdoms back in the sixteenth century, when Hernando de Soto rambled through. By the nineteenth century, though, epidemics and colonialism had emptied the Mississippi’s floodplain; the vines and cane grew so thick that early settlers had to pack axes and knives to cut clear paths.

The Yazoo River by then was the entry point for wealthy men who hoped to plant cotton on the rich Delta soils. They helped make the county along the mouth of the Yazoo—Issaquena, it was called—the second-wealthiest in the country, per capita, in 1860.

As always, such numbers hide as much as they reveal. In the wealth-per-person ratio, most of Issaquena’s residents were not then counted as people: Issaquena had the highest proportion of enslaved residents in the U.S. In the years since Emancipation, with Issaquena’s Black population officially flipped from the ratio’s denominator to its numerator, Issaquena has consistently been among the country’s poorest places. I don’t have the space here to detail the sordid economic history of the Delta, but suffice it to say that much of the twentieth century has been an era of consolidation here: land and money flowing into an ever-narrower set of holders, and generally away from Black hands and into white. In 1990, a geographer noted that the region was more segregated than it had been four decades earlier, before the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

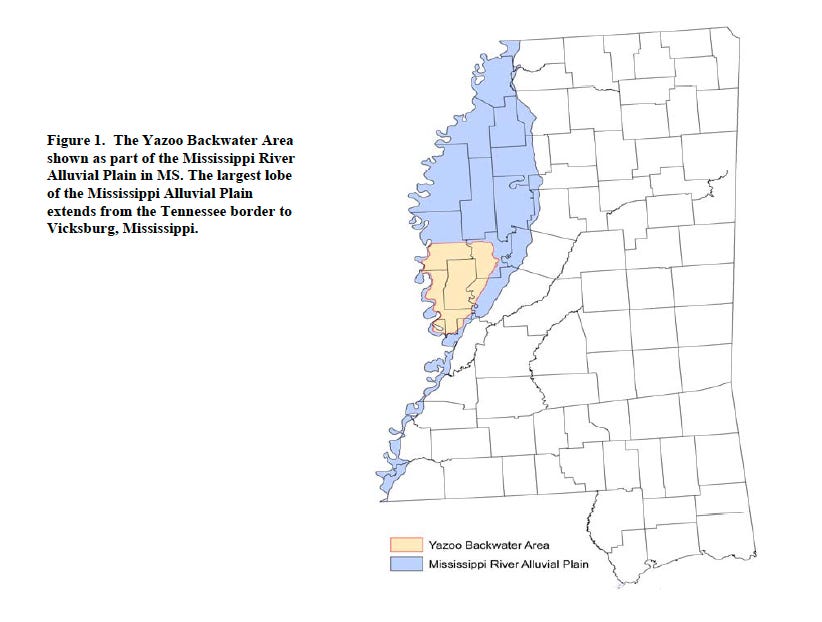

Through it all, the land along the mouth of the Yazoo River struggled. Around the turn of the twentieth century, as so much cotton acreage was cleared upstream, the river became the exit for all the water draining off the fields. In 1902, the land near the Yazoo’s mouth remained wild enough that Teddy Roosevelt could come here to hunt bears;2 one of the accompanying newspapermen compared the thick local forests to an African jungle. Today, Highway 82, which cinches across the Yazoo Basin like a belt, serves as a dividing line: to the north, Highway 61 carries four lanes of traffic. To the south, it’s a two-lane road that bisects quiet fields, where no traffic light slows drivers for a sixty-mile reach. Most of the substantial chunks of public land in the Delta are in or near the backwater area.

Back in 1928, in the wake of a massive flood, engineers were scrambling for a better approach to controlling the river. This swath of land, then, looked like a good place to sacrifice: little developed, it might become a place to store floods. Thus was born the idea of the “Yazoo backwaters.” During floods, the Mississippi would be allowed to push its waters up the mouth of the Yazoo, smothering this territory so as to lessen flooding downstream.

The wealthy men of Mississippi were, understandably, unhappy with this decision. That launched nearly a century of legislative and legal struggles.

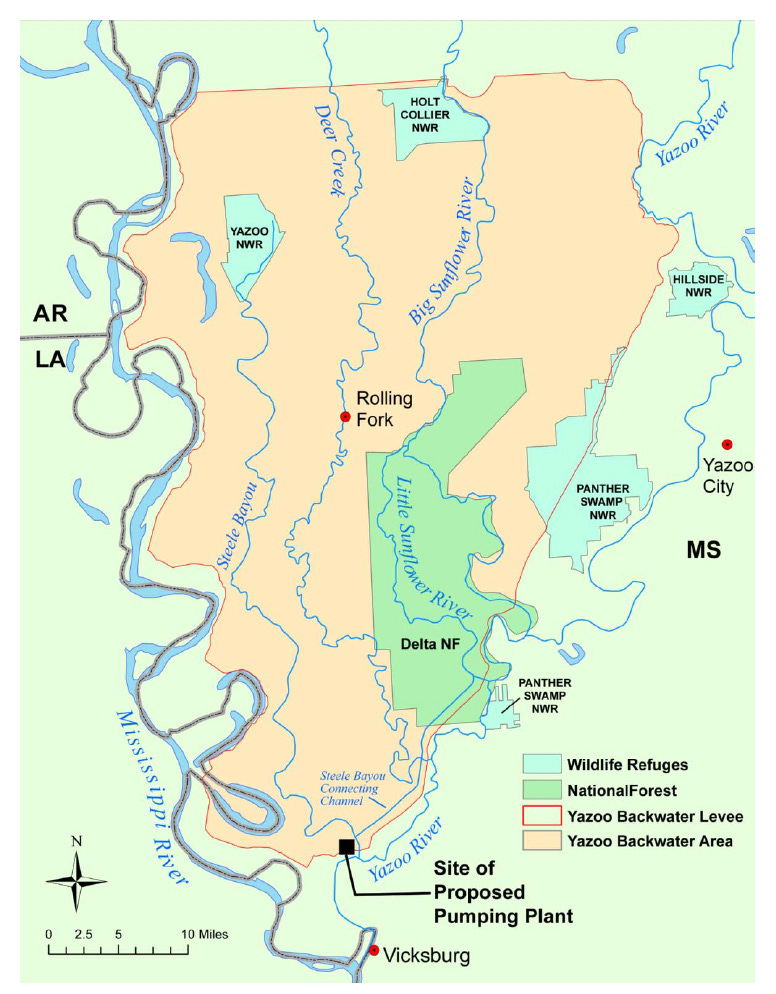

The first breakthrough came in 1941: a compromise. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers promised to build a levee along the Yazoo River that would prevent most of the big river’s backwash from pushing upstream. (The region, though, was still considered a backwater, and in a truly epic flood—the “project design flood,” as the largest disaster the system of levees was meant to contain is known—the Yazoo levees are meant to be overtopped.) The levees would be accompanied by a pump so that rainfall would not become trapped on the land.

These pumps were never built, for various reasons: first, in the 1950s, the Corps of Engineers decided they couldn’t be economically justified for such a barren place. Even the levee was postponed.

Two decades later, when soybeans arrived and made the southern Delta a place one could make money, the levee finally came up. But before the pump could be installed, conservative politicians made a successful push to abolish wasteful flood control projects. In 1986, locals were forced to bear most of the cost of the pumps—more money than this rural region could afford. In the 1990s, another law turned the fiscal responsibility for the pumps back to the federal government. Then, in 2007, the Environmental Protection Agency declared that the pumps would damage precious local swamps.

The New York Times had compared the pump project to “an indestructible ghoul in a low-grade horror flick,” since it seemed to be forever “rising again from the bureaucratic crypt.” But the EPA’s 2007 decision seemed final—the zombie finally slain.

Then came 2019, the year of big rains.

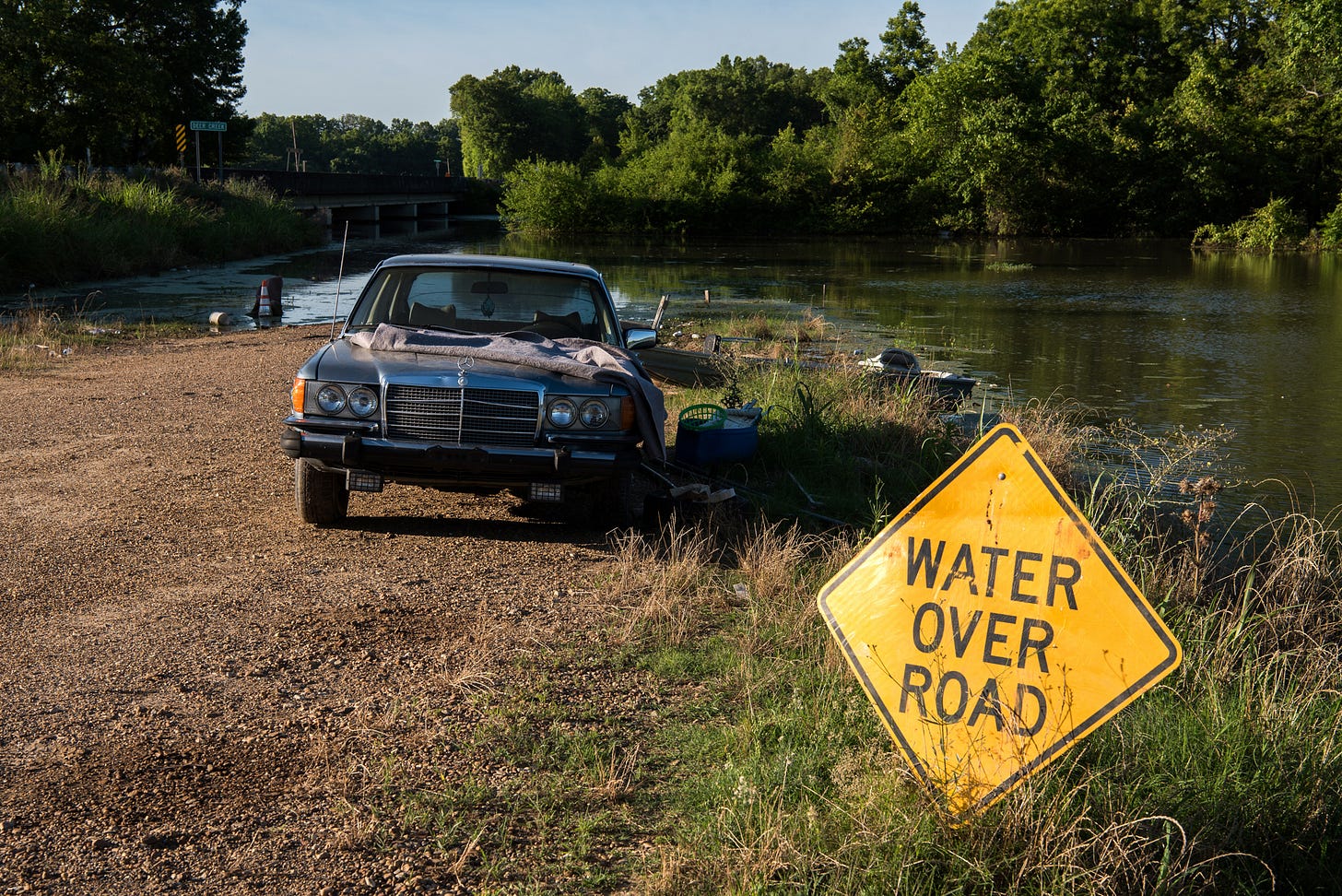

The storms along the Yazoo River began the autumn before, really, and by September, local soybeans had gone moldy. Come harvest season, the fields were often too wet to traverse. As autumn turned to winter, and then into spring, the pool of water atop the Yazoo backwaters grew to encompass more than 500,000 acres, an area larger than the island of Maui. In March, a man and a pregnant woman turned the wrong way while driving on a highway; their car slipped into the water and both died. Because this inland sea included 230,000 acres of farmland, the economic tragedy was more widespread. “Ain’t no money,” one farmworker told Mississippi Public Broadcasting in August 2019. “So we had to cut back on grocery shopping cause we had the light bills and the cable bills still coming in.”

The flood was brutal on wildlife, too. Since local levees were the only land that stayed above the water, deer were trapped there, clustered tightly, competing for food. Raccoons and turtles were stuck on the levees, too, a combination that led to most of the turtle eggs being eaten by the raccoons. Turkeys, meanwhile, were imprisoned in the trees, so they, too, began to starve. Even some of the trees themselves, soaked and stressed, grew infected with beetles. One Mississippi Levee Board commissioner came upon a “tree of death,” filled with hundreds of vultures, surrounded by hundreds of carcasses. “The things I saw I never want to see again,” he later said. The media was busy that year covering floods upstream, on the Missouri. Many locals took to calling their disaster the “Forgotten Flood.”

The devastation jolted the Yazoo Pumps ghoul back to life. A Trump-appointed EPA administrator promised to reinstate the permits and get the project rolling. Then, a year later, once the Biden administration took over, agency officials changed course again. Trump’s administrator, they said, had ignored the views of senior scientists and misinterpreted the law. The permits were revoked once more—a veto of a veto of a veto.

Earlier this month, federal officials announced a new compromise proposal: they could build a bigger pump than before, one that could move water more quickly, but that would allow the water to rise higher than in earlier plans. The new pumps would have different triggers during the growing season than during the off-season, too. I haven’t had a chance to study the ins and outs of the proposal, but at first glance, it does look like a more thoughtful approach.

Still, environmental groups, who have long opposed the project remain aghast.

“We are stunned that the Biden Administration would choose to advance a plan that abdicates its conservation, climate, and environmental justice commitments by willfully putting the vetoed Yazoo Pumps back on the table,” Jill Mastrototaro, Mississippi Policy Director for Audubon Delta, said in a statement. These groups say that the project is still a giant handout for local landowners. Certainly, it remains a massive federal expense that will benefit a region still marked by severe inequality.

One thing I can’t help but note is that there are low-lying areas in the Mississippi Delta that will not be served by the pumps. Holmes County is the one county in Mississippi poorer than Issaquena; in the town of Tchula, where almost all residents are Black (and sixty percent live in poverty), more than twenty homes flooded after a big storm during the 2019 floods.

Mayersville, the county seat of Issaquena, consists of a few blocks of trailers and bungalows that are all pressed against the river levee. When the Mississippi River rises, rainwater gets trapped inside the levee, unable to drain through the soaked soil. Most years, such “seep water” disappears quickly, as soon as the river drops. In 2019, the local flood stayed for nine months, according to Otis Parker, a 77-year-old farmer who lives in Mayersville. I asked Parker about the pumps when I toured the region soon after the floods, four years ago. “Ain’t going to help,” he replied. Ninety percent of the town’s residents are Black; more than 40 percent live in poverty.

The land here, as in Tchula, is too far away to be drained by the pumps. The flooding in Mayersville and Tchula was as much forgotten—if not more so—than the massive backwater pool, and offers a reminder that there is no clear definition of what constitutes a disaster, how many people must suffer, how much money must be lost.

“To name something a disaster is to decry its outcome as illegitimate, and to call for a restoration of the status quo,” as the historian Andy Horowitz has written, “instead of suggesting that the status quo may have been illegitimate in the first place.” When it comes to the Yazoo Backwaters, the floods are only one of several problems to be solved.

Yazoo, in actuality, was the name of a people who lived here.

It’s here that the president famously spared a bear, thus inspiring a famous stuffed bear toy.

Any idea as to why Biden approved the pumps given how against it the EPA previously was? And why the EPA is suddenly on board as well?

I’ll have to do more reading, but why not remove the levees if that’s the flooding issue? Because of downstream interests? The imagery of the dead animals reminds me of stories I heard when I worked in the central Everglades, when the WCAs were flooded because SFWMD wouldn’t open the gates to let the water flow south, tree islands were flooding and deer were trapped on the higher ones or levees. IIRC what I was told correctly, the Miccosukee tribe ended up putting out deer feed on the levees because it got so bad.

What a disaster. I had no idea about it.