Pin drop: Caddo Lake

Sometimes being on the edge—nowhere, uncertain—is what you really need.

A good map tells, if not stories, then tantalizing hints of stories.

Consider the landforms and waterways that curl through Caddo Lake, which crosses the border of Texas and Louisiana north of Shreveport. The names, as described by local Wyatt Moore, are colorful: a spot known as Judd Hole was “named after an old man called Judd, who was later found dead in his camp somewhere down there.” Several different inlets wound up with the name Whangdoodle Pass “because people who thought they knew where the original was got to calling different openings Whangdoodle.” As for Pig Turd Island—“kind of an odd name,” Moore admits—the origins are, unfortunately, lost to the past.

There’s a former steamboat landing on the western edge of Caddo Lake whose name doubles as a meta-commentary: No one knows with certainty how Uncertain, Texas, got so designated. Perhaps it was because it was difficult to arrive at the dock; or maybe because back in the early nineteenth century, locals weren’t clear whether they lived in the United States or the Spanish colony of Mexico. The countries disagreed on the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase, but rather than fight both agreed to leave the border zone alone. So it became the “Neutral Zone” (sometimes called “No Man’s Land”) and attracted the sort of settlers who were happy to have no government looking over their shoulder.

Even now, as the city’s official website admits, finding the place “can leave a lot of people feeling...uncertain.” I concur. The main route into town is a narrow, pine-laced road where, based on the state of upkeep, it’s hard to decide whether the adjacent buildings are abandoned or just in an extended seasonal dormancy.

Even now, as the city’s official website admits, finding the place “can leave a lot of people feeling...uncertain.”

It feels like a road to nowhere, and it nearly is. Uncertain, though governed by a mayor and a five-person city council, has a total population of just 85. It’s basically a scattering of RVs and buildings across several loops of road. Perhaps visitors become abundant on weekends, but on the overcast Thursday when I arrived last May, the place was about as sleepy as sleepy gets.

I’d come to Texas for a magazine story—a road trip along the border of Texas and Louisiana, an exploration of the cuisine of this little-known region. That story was published online last month, which put Caddo on my mind again; then I noticed that the video for the new single from Waxahatchee uses Caddo as its backdrop. I had been meaning for a year to write about this place, and now seemed like as good a time as any.

Caddo itself has had several names through the centuries, which reflects the fact that it’s lived several lives. But that is not to say its story is epic or ancient.

Credit its birth to the loose soils of the southern Great Plains, which, in the wake of a heavy rain, are all too willing to give up their trees. For centuries, the deadfall washed down the Red River, eventually accumulating into what early settlers called the “Great Raft.” I find that a rather small name for something so geologically monstrous: Think of a beaver dam, but one that filled more than a hundred linear miles of the river. During early cattle drives into Mexico, cowboys walked across the raft without fear of drowning. Visitors noted willows and cottonwoods sprouting from the older, rotten wood, with trunks as broad as eighteen inches—a forest growing atop a river. The rotten logs trapped the river’s mud, too, creating shoals that pushed the water outward. Scientists have analyzed that wood, which has provided an estimate of the age of Caddo Lake: some time around the dawn of the nineteenth century, the accumulation blocked the mouth of Big Cypress Bayou, backing up its water, creating not just Caddo, but a whole a chain of lakes.

The waters alongside Uncertain, Texas, were first known to white settlers as Fairy Lake, for reasons I have not been able to ascertain. I like to think that all the Spanish moss strung through the cypress trees gave the place a sense of enchantment—though given the lawlessness, the enchantment must have only gone so far. One of the lakeside villages became known as “the place where they kill a man every day.” It was renowned for its brothels and gambling dens and cockfights, but to enjoy that revelry, you had to risk the fact that, on average—at least according to the rumors—one person wound up murdered daily.

The Caddo name, I should note, honors the Caddo People. But, as electrician and lake aficionado Fred Dahmer writes in Caddo Was, one of the more thorough book-length treatments of the lake, “when it became apparent to the wise old Caddo chiefs that the white settlers would continue to overrun their land, they agreed to a meeting with an agent of the United States to discuss a treaty for the sale of their land.” (I tend to think the decision was a bit more fraught than that.) That was in 1835. Not long afterward, it began to look like this morass of swampland might become a respectable redoubt of the genteel, cotton-growing South. Steamboats began to pick their way through the log-jammed bayous, ultimately reaching the town of Jefferson, which lay a few miles beyond the lake. As planters rushed west, seeking new ground, Jefferson became the second-largest port in Texas, a hub for cotton being shipped downstream.

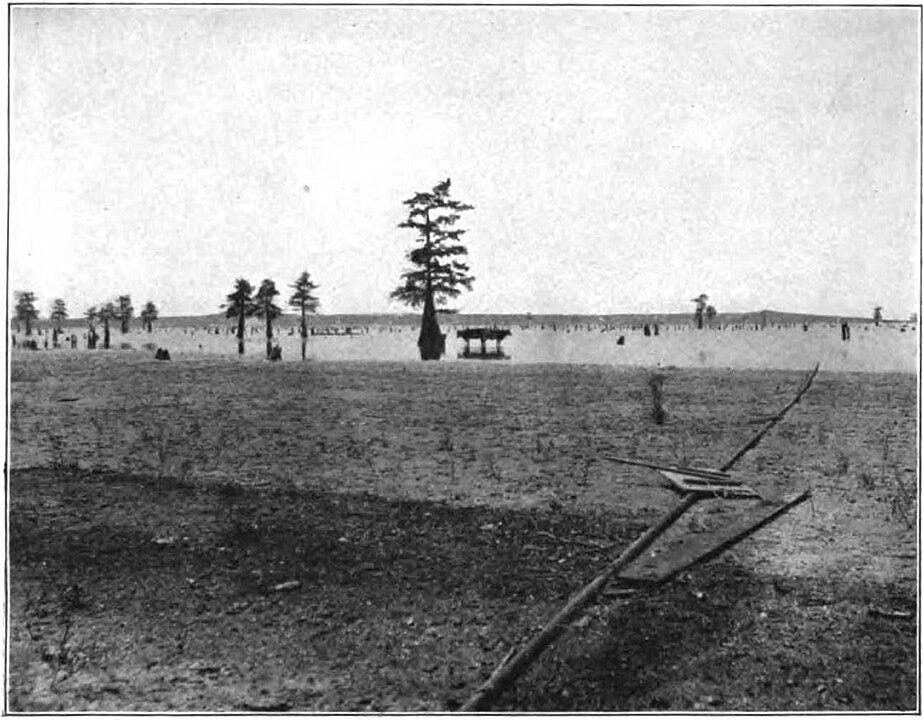

The federal government had long been working to remove the logjam from the Red River; in the early 1870s, with the aid of nitroglycerin, the project was finally finished. But this proved disastrous for Jefferson. The stopper had been pulled: The chain of lakes began to drain. Fairy Lake, at least, had been filled with enough shoals of mud to retain some water. But the region had only ever been navigable for part of the year; now, with each passing year, the season grew narrower, until the boats stopped coming at all. (Some for a time lay abandoned atop the exposed mud.) It was “a tragedy from which Jefferson and all our area has never recovered,” as Dahmer put it.

From my rather selfish point of view, though, this was the moment that lent Caddo its appeal. It’s what brought Waxahatchee here, too, I’d guess: it left the place as an appealing nowhere.

I can get rather squirrely on a road trip, especially a road trip that, like this one, is official business. I’m beset by warring impulses: I want to fulfill my professional duty, and find the best possible experience to share; and yet the best possible experience is so often lazy serendiptiy, impossible to plan. Such was the case at Caddo: I had vague plans to rent a kayak and explore the lake’s byways, but a grim web of clouds in the sky gave me pause.

For the kind of travel story I was doing, it’s standard procedure—maybe even best practice—to call ahead and find some charismatic local who can wax poetic about the landscape, or, failing that, at least an ecologist who can list the names of species. I’m an introvert, though, so I called no one, a move I justified as an appropriate approach to a place called No Man’s Land.

“Nothing about the lake encourages visitors,” Dana Rubin wrote in Texas Monthly back in 1992. She warns, rightly, that it’s a difficult place to experience. Patience is necessary: there is no scenic overview, no simple way to take it in. There is an old saying that if you head out onto the water and don’t stick to the clearly dredged canals, you’re liable to spend a night in the “Caddo Motel”—wet and lonely amid the howls of the alligators.

The fact that there is still a labyrinth here of waterlogged forests is, surprisingly, thanks to the oil industry. Drillers found black gold beneath the lake a few years into the twentieth century. In 1914, tired of schlepping their equipment across a long morass of shallow sludge, an oil company decided to build a dam in Louisiana. Caddo’s slow drain stopped—and so the lake was saved.

There are whole heaps of Caddo history I’ve left out here, for the sake of space—pollution from a military munitions plant; a plan to dredge a barge canal through the lake, which critics dubbed a “superhighway to nowhere”; the formation of a conservation nonprofit, in part thanks to Don Henley, singer and drummer for the Eagles, who grew up near the lake; the lake’s designation, in 1993, as a “wetland of international importance.”

I stopped by Johnson’s Ranch—which bills itself as the oldest inland marina in Texas—and bought a waterproof map of the lake. But that wound up the extent of my explorations: I sat on the dock, considering the greying sky, tracing the contours of the waterways, with all their odd names, watching the unmoving water. I was happy enough there. Nature is supposed to be ancient and timeless, and a good Southern swamp can feel like a vestige of the Earth’s older and oozier days—back when all life moved in wriggles and creeps. But at Caddo, as in any wetland, the only thing that is truly timeless is change. Sometimes just sitting there, still for a moment amid that change, is more than enough.

If you go

Lacking an RV, which seems to be the lodging of choice in Uncertain, I stayed just up the road, at Caddo Lake State Park. If you’re lucky, you’ll be able to snag one of the fine campsites along a millpond fed by Big Cypress Bayou. It’s a quiet park, with a few miles of trails for walking.

As for food, I put it this way in The Local Palate: “This is redneck country in the best way, a place where savvy cooks know their way around a bun.” I only eat about one hamburger a month these days, and I was not disappointed to make the Lake Caddo Lighthouse, a delightfully dingy bar that seems to have a thoughtful chef manning the short-order grill. The Shady Glade Cafe is another reasonable option.

For those seeking less rustic accommodations, Jefferson today is filled with bed and breakfasts, mostly built into old nineteenth-century architecture. But even if you want to rough, plan to drive into town for a taste of Riverport BBQ.

“based on the state of upkeep, it’s hard to decide whether the adjacent buildings are abandoned or just in an extended seasonal dormancy” Love this line and imagery.

Those black dots are indeed oil rigs - original models for the larger rigs found in the Gulf today, or so I've been told. My family's from Mooringsport, one town over from Oil City, and I have a lot of early memories of paddling through cypress knees in a john boat with my grandfather.