With its odd and sometimes grotesque knees, with its omnipresent haze of Spanish moss, the bald cypress—Taxodium distichum—rivals the live oak as perhaps the prime botanical symbol of the South. It’s a survivor, hearty and water-growing, fiercely holding its grip in soft soils even after hurricane winds, a good fit for this soggy and storm-battered region.

Its wood is a survivor, too, naturally rot- and pest-resistant. That helped give the cypress, or at least its surrounding ecosystem, a countervailing distinction. As National Geographic recently pointed out, swamps are perhaps the only landscape that has been “specifically targeted for destruction by the federal government.” Beginning in 1849, the government transferred much of the nation’s swampland to the states. They were to be sold, the proceeds used to build flood-control infrastructure—a move meant to supercharge the country’s agricultural economy by opening up new lands for planting.

Tucked at the foot of the loess bluffs just north of St. Francisville, Louisiana, is a peninsula of land formed by one of the Mississippi River’s big bends. A smaller waterway, Bayou Sara, runs parallel to the foot of the bluffs, placing the forests here almost but not quite atop an island. Close enough, it seems, for the place to become known as Cat Island. Most of Louisiana’s bald cypress trees were harvested over a fifty-year period in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, and, Cat Island is no exception. Second growth now dominates. The only ancient trees left behind were those too hollow to be profitable to harvest.

In the 1960s, the Corps of Engineers cut a canal into the peninsula, hoping to tame this swamp. The scheme was canceled over worries that the canal would form a cutoff, altering the path of the big river. (Still, the canal forever altered the hydrology of the swamp, leading to extended periods of dryness. “Swamp ain’t no good without water,” as one local told NBC News back in 2004.) So in the 1980s, this was still wild-feeling forest, even if it had lost its oldest trees.

Though not, as it turned out, all its oldest trees. That decade a pair of foresters working for Georgia-Pacific stumbled on a massive old cypress tree—an ancient behemoth of such startling proportions that it set a national record. Then, a month later, the same foresters found an even bigger tree. Today, it’s the third in their sequence of discovered trees that holds the title of champion.1

In 2000, after the Nature Conservancy bought up some of the land on Cat Island, Congress created a national wildlife refuge, which continues to expand slowly. I try to make a trip to the refuge once a year or so. (I’m currently overdue.) The pleasures of the trip in many ways lie outside this swamp: St. Francisville is a cute little village, with several decent restaurants; one of my favorite hikes in the region is a trail through the loess bluffs just to the north. Cat Island itself is, like many national wildlife refuges, not managed for the sake of aesthetics. The roads, when they’re passable at all, pass thick stands of forests with few arresting sightlines.

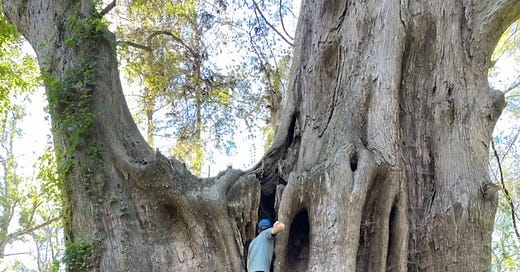

Still, the tree itself is core to the ritual. It’s impossible to accurately age this champion, since it lacks the needed tree rings, but most sources agree that it’s at least a thousand years old. That’s part of what lures me, surely: here is a grand being that has witnessed so much change along this river.

I will note that there is a danger in obsessing over what Jared Farmer has called “anthropomorphic treeness”—in focusing too much on a single tree, because of the mistaken notion that it is analogous, somehow, to our singular human selves. Trees are not meant to be solitary, but, as Farmer notes, “modular [and] social [and] communicative.”

That won’t stop me from seeking out grand old trees—just this weekend, in fact, as I was drafting this essay, I made a quick visit to Louisiana’s other champion tree, a live oak—because I think any excuse to venerate the more-than-human world is worthwhile. It does offer a reminder that, in addition to loving old things, we need to find a way to, as Farmer puts it, “give care to young things that might grow old.”

The champion cypress has been described as “squat [and] oddly proportioned.” To me that’s part of its appeal. Cypress trees aren’t tidy beings; they have a gothic grandeur, a profusion of protuberances and folds and hollows.

Though perhaps there’s selection bias at work here; the only venerable cypress left are those with what one prominent cypress researcher calls a “gnarl factor”—they were useless to the needs of the logging economy. Maybe if I get to stick around long enough to see some new old cypress forests, I’ll learn that these trees are even more beautiful than I know now.

Coordiantes

If you go

Just north of St. Francisville, across the border in Mississippi, is Clark Creek State Park, which allows visitors to explore the rugged terrain of the loess bluffs. The full loop is not very well blazed—so be cautious and leave yourself plenty of time before sunset, in case you get lost, as I always have.

I’m also a fan of the Oyster Bar, which sits along the banks of Bayou Sara near its confluence with the Mississippi. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “casting fields,” where the agency creates the concrete materials they use to protect the riverbanks against erosion, are just up the road.

What about the oldest cypress?

For another superlative cypress tree, head to the Black River in North Carolina, where a dendrochronologist verified that one tree is at least 2,600 years old. These cypress’s rings offer a climate record of the region—including a drought that may have thwarted the first English effort to establish a North American colony, in 1587. The land is owned by the Nature Conservancy and is serviced by several outfitters.

National champion trees are, like so many metrics, rather more complex than they seem on their face. The title is granted based on a score that combines the tree’s circumference (626 inches) with its height (91 feet) and the spread of its canopy (87 feet).

Marvelous! I didn't know there was such a thing as a "dendrochronologist." Also ... "...any excuse to venerate the more-than-human world is worthwhile -- YES! Thank you.

So flipping amazing. Thank you for this.