Populism & Southern Lands Pt. 2: Walking on Easement Street

In southern Florida, federal landscape protection is seen as a win by all sides

Last week, I took a look at a simmering conflict in northwestern Arkansas, where locals are worried that wealthy out-of-towners will turn their rural surroundings into a kind of nature Disney park. (An update on that: the Newton County Quorum Court—the county commissioners, in essence—unanimously voted to oppose any redesignation of the Buffalo National River.) In part two of this series, I want to highlight an opposing story, a place where efforts to preserve land are meeting little controversy at all.

To understand the context, you need to know about what the Biden administration calls the “America the Beautiful” Initiative. This is a broad effort to conserve 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030 for the sake of biodiversity and climate resilience. Don’t picture a carefully formulated scheme; the administration has simply encouraged federal agencies to take what actions they can that support that goal.

I noted last week that around half of the U.S. West is federal property. But much of that land is open to cattle grazing, which hardly constitutes “conserved” land. So even beyond the Mississippi, it will be hard to protect 30 percent of the land without cooperation from private landowners. Here in the South, such cooperation is essential: ninety percent or more of the land in most states is in private hands.

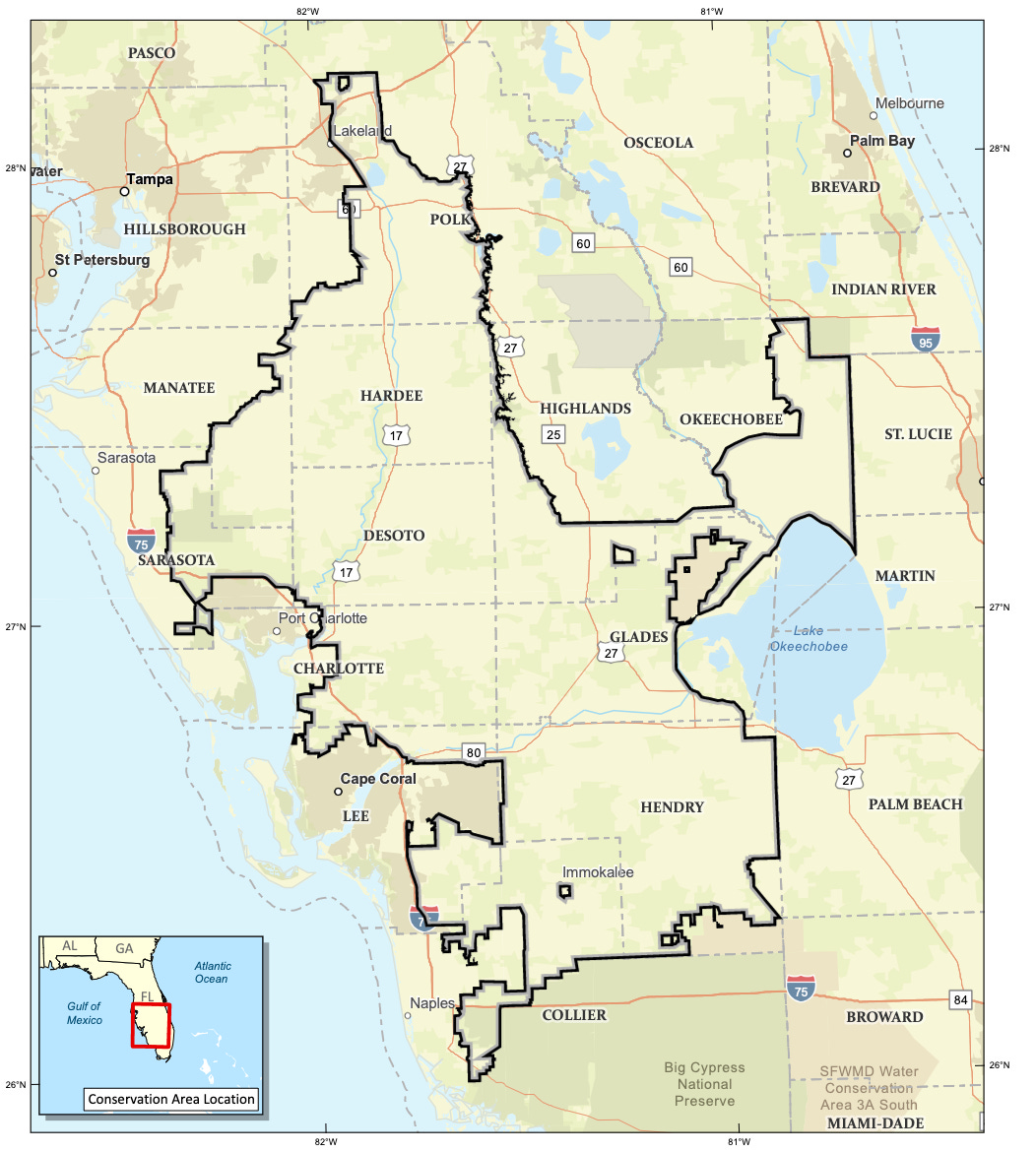

In late September, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released draft plans for what it called the “Everglades to Gulf Conservation Area,” a four million acre adjacent to an existing wildlife refuge containing expanses of intact natural landscapes and watersheds. There is wetland forest, wet prairie, freshwater marsh, pine forest, and agricultural land; the area is home to over 70 threatened and endangered species, including the Florida panther. The idea behind the conservation area is to create a corridor linking existing protected lands.

You might look at the map above and think, Hey, that’s a big wilderness. But the outlined area is just the boundaries within which the USFWS will conserve what it can. Within this zone, the agency is offering willing sellers “conservation easements”—payments around 40% of the full market price of the land, in exchange for giving up the right to develop their land. (USFWS is also seeking full “fee-title” acquisition of land from willing sellers, but only for 10 percent of the area, or 400,000 acres.) An easement does not create public land—the owners still determine who is allowed to access their property1—but it can help ecosystems remain intact.

Self-described defenders of “property rights” detest conservation easements, given the restrictions they place on certain uses of the land. “If you must get permission to use your land, you don’t really own the property,” as one conservative group puts it. (The America the Beautiful Initiative, meanwhile, is described as a nefarious land grab.) Nebraska has become a hot spot of opposition; some landowners have had their requests for easements declined by county officials, because they’re tying the hands of unborn future property owners. In Florida, though, the Everglades to Gulf Conservation Area has earned widespread support.

Florida is a unique place: it’s a natural wonderland, but also the site of a unique ranching culture; it’s one of the fastest-growing states in the country, which puts pressure on both the nature and the ranchers. Locals have worked hard to unite two groups that might not typically see eye to eye—cattle ranchers and conservationists. Specifically, the new easements will allow what the Fish and Wildlife Service calls “working lands” to stay at work. Farms can still be farms; ranches can remain ranches.

“A Florida panther can walk across a ranch and be relatively safe,” as one local conservationist explained to Inside Climate News. “They can walk across a citrus grove and be relatively safe. But you can’t have them walking through neighborhoods without conflict.” It’s another reminder of the complexity of land use: you’ve got public versus private; pristine versus human-impacted; rural versus “developed.” Within those dualities there can be divisions, but also ways to come together.

+Though the conservation easements will protect agricultural acreage, farming is not a simple thing. Landclearing in the “Everglades Agricultural Area,” just east of the proposed conservation area, is now identified as a major carbon emitter. (Inside Climate News)

around the Southlands

🐢 The Turtle Heist: Writer Sonia Smith delves into the underworld of alligator snapping turtle poaching in Louisiana and East Texas. (Texas Monthly)

🦪 Diverting the Diversion: Plaquemines Parish is suing the state of Louisiana, seeking a halt on construction of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, the largest restoration project on this troubled coast. Oyster harvesters, too, have announced their intentions to sue the state. (Times-Picayune)

+Louisiana Governor-elect Jeff Landry has stocked his “coast and environment” transition council with industry representatives and lawyers—but no conservationists, scientists, or Indigenous people. (Times-Picayune)

🥾 Preserving McAfee Knob: One of the most iconic viewsheds on the Appalachian Trail has been preserved—in part with money from a controversial pipeline payout. (Backpacker)

🦌 Deer gone wild: Farmers in Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas are complaining about destruction from deer. It’s “one of the most pressing issues” that local farmers face, says one lobbyist. Yet populations are stable, perhaps even in decline. (NPR)

Generally, the organization that holds the easement will have the right to enter the property for purposes of upkeep and maintenance.

Your posts are very helpful, as usual.