The Alabama graphite belt

The quiet woods of the southernmost Appalachians might fuel your future EV

A billion years ago, most of the land on this planet was mashed together into one massive island. One way to date the birth of Appalachia is the breakup of this island—Rodinia, geologists call it, from the Russian for “motherland”—roughly 700 million years ago. The incipient mountains were a new crack in the Earth’s crust.

This was a ragged edge, containing low troughs but also promontories. Alabama— today the southernmost edge of the Appalachian plateau, harldy known for rugged terrain—was one of these high points. Over hundreds of millions of years of drifting and crashing, of vulcanism and erosion, a chain of mountains as grand as the Alps arose, then weathered down to the wizened old humps we know today.

Those early peaks in Alabama must have contained some thin layers of ocean silt, which along with the surrounding rock was “intensely folded and faulted” through the epochs. That’s how you make flake graphite. Today, a thread of this crystalline rock—its carbon atoms sit in layers, arranged in a honeycomb-like pattern—runs for seventy miles through Alabama’s low mountains.

This is a little-known expanse of southern Appalachia, though the quiet may not last. Nearly a third of the weight of modern electronic car batteries, up to 200 pounds per car, consists of graphite, so the mining boom is coming for these tired old rocks.

The Inflation Reduction Act included a future tax credit for EVs built with domestic materials. It had to be future, since that’s not possible yet. Most of the world’s graphite is currently mined in China, and the entire supply of graphite is processed there—which, as EVs take off, makes a lot of politicians a lot of nervous.

That’s why several companies are eyeing Alabama. Westwater Resources is furthest along, having explored the local mineral prospects for nearly a decade, and holding claims to over 40,000 acres of mineral rights. Mining is not projected to begin until 2028, but Westwater is already building a processing facility nearby, where imported graphite will be refined until the local supply kicks in. (The graphite belt is not far from an existing hub of automotive construction.) A second company, South Star Metals Battery Corp, has begun exploratory drilling and claims promising results.

There are other U.S. graphite stores—in Texas, Pennsylvania, New York, and Alaska—but Alabama is the closest to ready, given its history. In the few eras that the U.S. has had a domestic graphite industry, this has been its epicenter.

Alabama’s flake graphite entered the geological record during the Civil War, when a geologist in the employ of the Confederate government was scouting the region for sulfur. Commercial production launched in 1899, after local mills developed a workable method for separating the small bits of graphite from the surrounding schist.

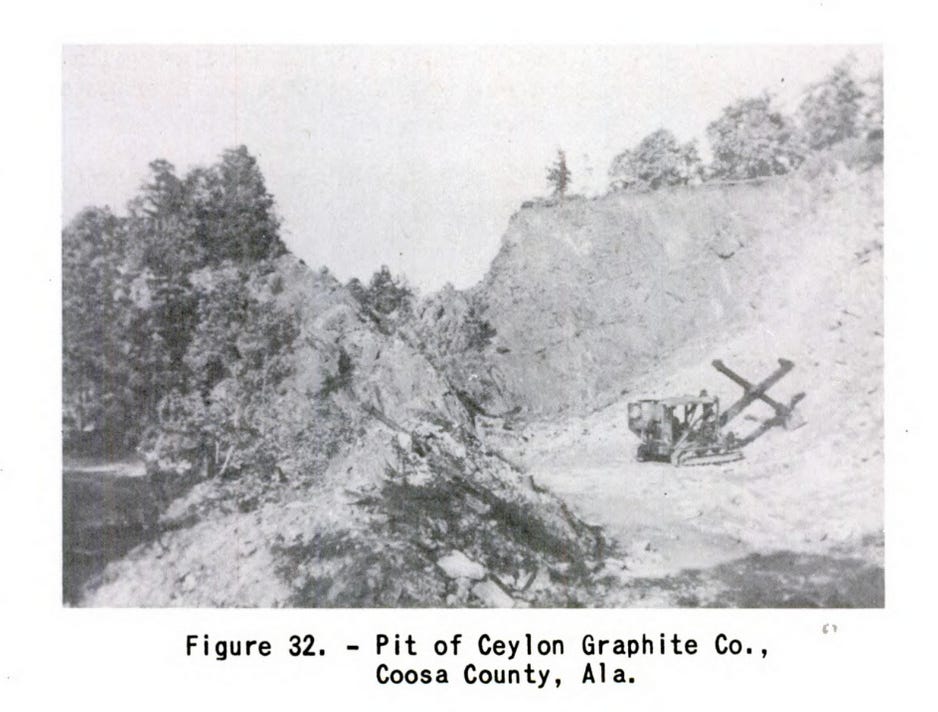

Eventually, more than 50 mines opened across the region, which supplied graphite for steel-making, lubricants, and gunpowder. These were open pits: since the granite lay just 25 to 100 feet below the surface, drills and explosives were rarely necessary; just a pick and shovel would often do, or if not that then a mule with a scraper. (Later, excavators were used, too.) The industry surged during World War I, but after the war, when cheap imports from Madagascar resumed, many mines shuttered. There was another spurt of mining during the next global war, but by 1953 the industry had disappeared again.

Westwater, too, will mine open pits (and their equipment will be powered by diesel generators, ironically, at least until the mine grows large enough to link up to the electrical grid). I haven’t seen environmental studies of the mines yet—though those will come before any permits are granted—but graphite mines in China have marred the air and water.

The Alabama graphite belt is a quiet expanse of ridges and valleys, which stretch northeast toward the Appalachian range. It’s not particularly dramatic; the altitudes near the future Westwater mine are between 350 and 1200 feet. The forests are mostly second growth, often pine plantations; the largest nearby towns have less than 15,000 residents. Even if it’s not the kind of landscape tourists flock to, it is patch of land where wildlife can thrive. Some of the Westwater claims lie on a state wildlife management area, managed for deer and small game, and known as a local birding hub. The Coosa Riverkeeper, an environmental nonprofit, points out that the nearby creeks are some of the state’s most pristine, breeding ground for red bass, home to a rare stand of spider lilies. A dozen endangered species may live within the area the mining companies are exploring.

It’s an increasingly familiar conundrum: in a “green” economy, we need to get our resources from somewhere, so how do we decide where? Is it any better, for this planet or its population, to source this graphite from China? The Coosa Riverkeeper has expressed support for clean energy, but, given that their mission is to protect this watershed, they’re keeping a critical eye on how the next era in this nook of ridges unfolds. I’ll be watching, too.

If you go

The Alabama graphite belt is not much of a tourist zone. I visited the Coosa deposits last month and the closest thing I could find to a tourist trap was the “grave of Fred the Town Dog”—a story whose details I’d like to know.

Still, if you want to see this terrain before it’s mined again, there are some viable approaches: the Pinhoti Trail connects this ridge to the Appalachian Trail. If you start your hike on the trail’s southern terminus you will wind your way through the northern portion graphite belt.

The Westwater claims, meanwhile, sit alongside Weogufka Creek, which a preliminary assessment of the mine, conducted on behalf of Westwater, calls “a priority item under consideration for all site layout activities.” The creek has been developed as a paddling trail, and the Coosa WMA includes several public campsites, including alongside the creek.

The South in the green economy

Another key metal for our “greener” future is lithium—which can be found just west of Charlotte, N.C., the site of another ongoing mining play and an emerging controversy. Know anyone impacted by EV mining in the South, or worried about how it will affect their home? I’d love to hear their stories.

It'll be interesting to see how this plays out. It's not obvious to us that EV enthusiasts have properly calculated the resistance to mining in the U.S. Especially not at the scale necessary to shift large percentages of U.S. miles traveled to electricity.

Great article!

Mining was built for the fastest extraction of resources at the lowest possible cost, and the tradeoffs were worker lives and environmental damage. Just as mine safety has progressed over the last 100+ years (Bureau of Mines, Coal Act, Mine Act, MINER Act, etc.), so should environmental protection be an inherent part of resource extraction. Responsible mining that minimizes and remediates damage to the environment is possible. Ideally, industry groups would hold themselves to a high standard and resource companies would act as responsible stewards of the environment where they work. More likely, legislation and government oversight will be needed, and conservation groups will have to hold public officials accountable. In Alabama, that is a constant fight, often taken to the courts. But the tension between development and conservation is a healthy thing--the question isn't either/or, but how we can satisfy both.