Once upon a time, back in the glory days, a brave hunter willing to tangle with an alligator could earn $60 for every foot of hide he or she brought in. These days, though, alligator skins aren’t such a hot commodity. You’re looking at as little as $10 a foot, according to the Florida Times-Union.

Thanks to a local celebrity, I recently fell down a gator-hunting rabbit hole. For a few days in April, there was a sizable reptile roaming the little waterway that runs a block from my house in New Orleans—a bayou where I regularly float my kayak and let my dog take cool-off swims. This alligator was nine feet long, according to the state department of wildlife, and quickly became a local spectacle. Then, on April 20, a team loaded the beast into a pickup truck. A decal identified the truck as belonging to the “Angry Gator Leather Co.”

The state wildlife department indicated to reporter Richard Webster that the team consisted of contracted alligator hunters. When I followed up with the department, I learned that such hunters are paid $100 for every gator they successfully capture—not bad prices, really, given the going rates for alligator hides. The hunters are also allowed to sell the meat or hide for further income—typically the preferred outcome, since gators have, per the agency statement, “remarkable homing instincts.” Nonetheless, to the delight of many of the New Orleans gator’s fans, it turns out he was set free in Lake Maurepas.

The alligator is, as one book put it, “among the last living representatives of the Mesozoic archosaurs”—the same broad group of animals to which dinosaurs belonged. (Besides crocodiles and other related beasts, the only other living archosaurs are birds.)

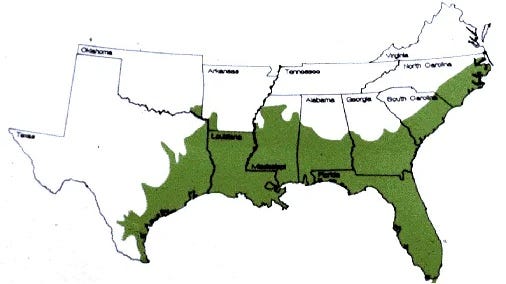

The American alligator, or Alligator mississippiensis, is particularly known for its ability to tolerate a range of temperatures—as low as 40°F, thanks to a little trick in which the alligators angle their bodies in the water, breathing through their exposed nostrils while protecting their bodies in the lower, warmer waters. (Still, an American alligator much prefers temperatures in the 90s.) This makes the American alligator one of the most northernmost crocodilians in the world, perhaps the northernmost.1

The market for gator hides goes back centuries: as early as 1800, a trapper could get as much as a buck a foot for the skin. The market grew so robust that by the 1960s, as the first U.S. endangered species regulations were first developed, these reptiles needed protection. Thankfully, once hunting was controlled, the American alligator turned out to be a species relatively easy to save. By 1975, some game commissioners in Tallahassee were spending half their time dealing with “nuisance” alligators.

What is a nuisance gator, though? Typically any gator under four feet long is considered too small to be a threat. Beyond that size, though, a nuisance is harder to define. Louisiana’s wildlife department offers guidance meant to help concerned residents distinguish between a truly threatening gator and one that just happens to be basking for a week in your backyard. “[W]ait a few days, even a week, if possible,” before calling in a complaint, the agency advises. But, generally, once a complaint is filed, the gears start turning: if you don’t like a gator, he’s going to be dubbed a nuisance, and likely killed.

In Louisiana, a thousand nuisance gators are collected in a typical year, and most are six to seven feet long. Florida seems to be the real epicenter of problem gators, with nearly 8,000 collected most year—even though the state only awards $50 per captured gator. (Until earlier this year, the rate was just $30—a payout that hadn’t budged in decades.)

One study found that the rate of nuisance gator complaints tripled between 1978 and 2013. One reason is that gators are thriving: from 1971 to 2014, Florida’s alligator population increased 271%. The real problem, though, is that over the samperiodod the state’s human population grew by 288%. So while the frequency of bites has increased, the likelihood that you will be bitten has not.

With cougars and wolves now limited to narrow slivers of their former domains, the American alligator is one of the last apex predators roaming the South. They tend to be a beloved species when they stick to remote waterways. Unfortunately, their status as a “nuisance” is likely to increase in the coming years: the spatial expanse of Southeastern cities is projected to more than double over the next four decades. And, so far as I could find, no one seems to have found a good way for these carnivorous reptiles and your average city dog to peacefully co-exist.

To see them

With our New Orleans monster gone, you’ll have to look elsewhere for gators, though this is one animal that should not be hard to spot. Parks across the Southeast—including, iconically, the Everglades—have plenty to spare.

I would suggest that if you choose to go on a swamp tour seeking gators, you find a company that does not feed wild animals—an act that habituates wild creatures to human interactions. The only tour group in the New Orleans area that qualifies, so far as I know, is the Last Wilderness Swamp Tours in the Atchafalaya Basin. (If y’all know of other ethical swamp tour companies across the South, please let us know in the comments!)

By the way, if you see an urban gator, steer clear, and you’ll almost certainly be fine. Between 1948 and 2004, there were 376 alligator bites recorded in the U.S., mostly in Florida. One analysis found that bites more than 6.5 feet from a shoreline were quite rare, and there were no cases at all of the gators running down their victims.

Around the Southlands

Louisiana history

A piece of a skull found along Lake Pontchartrain dates back 3,500 years—back to the era of Poverty Point. (The Advocate)

An insurance hit

Flood insurance rates are set to more than double across Louisiana, and in Pointe a la Hache, the southernmost town on the Mississippi River’s east bank, rates will increase by more than an order of magnitude. (The Advocate)

+ State-chartered insurance associations in Louisiana and Florida may have to borrow more than a billion dollars. “We’re currently in the midst of an insurance crisis,” the Louisiana commissioner says. (E&E)

Mixed records

Gov. Ron DeSantis is terrible on the climate—among other things. But Florida conservationists are quite happy with what he’s done for the Everglades. (Bloomberg)

Though, since the alligator has been around for so long, there have been eras, tens of millions of years past, when alligators were capable of roving as far north as the Arctic. It’s a reminder that—despite the ongoing crisis of climate change—the current world is far cooler than in many periods.