Field Guide: the Smackover Formation

An ancient, hidden coastline is about to fuel an Arkansas mining boom

Apologies for my absence over the past few weeks. I was wrapping up edits on my book (!) and then traveling for my honeymoon in Alaska. I’m finally getting caught up and should be back to regularly scheduled newsletters next week.

The geology of the South can be subtle. Our mountains are old and weathered. There are places—like the southern edge of Arkansas—where for hundreds of miles the land is so flat and unchanging that you can forget it’s geological at all.

But there’s always a story in the terrain—or underneath it.

For millions of years, the Gulf of Mexico reached far northward, covering much of what is known today as the coastal plain. That means beneath today’s soils lies an ancient seabed—mud that has since hardened into, among other materials, a limestone aquifer.

The “Smackover Formation” is one such belt. It curls from east Texas to Florida. The rock, which contains fossils from the Jurassic Period, now lies as much as 20,000 feet underground.

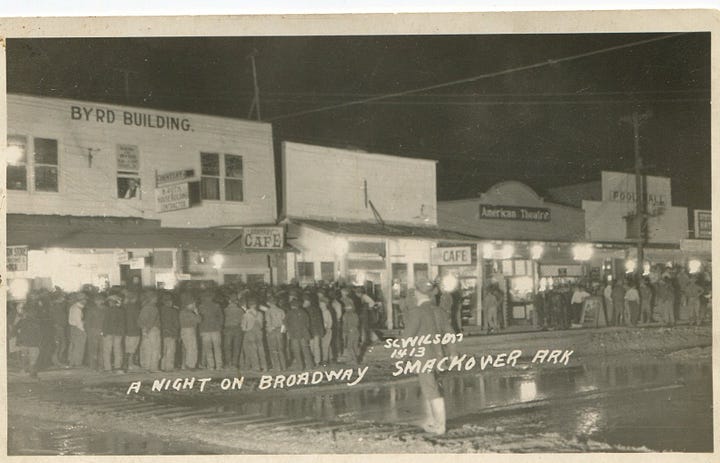

The formation is named for the town of Smackover (whose own name is somewhat shrouded in mystery1), which was incorporated in 1922 after a sawmill owner’s wildcat drilling yielded a burst of oil. The resulting boom town was lousy with gambling dens and saloons, at least until that November, when a self-appointed “cleanup committee”—members of the Ku Klux Klan, historians now speculate—decided to run the undesirables out of town. The vigilantes destroyed buildings and killed at least one person, and prompted a multi-day riot. In 1936, the Smackover Formation itself was identified and named.

The local extraction industry has since gone through several ups and downs. It’s trending upward lately, though not because of oil. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that ExxonMobil paid $100 million for a 120,000-acre property in southern Arkansas, near Smackover. They’re after lithium, an essential component for electrical vehicles. Some estimates suggested that demand for lithium will grow 20-fold by 2050—and perhaps as much as 40-fold. This one property alone could yield four million tons of lithium carbonate, enough to power 50 million electric vehicles, according to the Journal.

ExxonMobil is not alone. An official from another company, Standard Lithium, told BloombergNEF in 2021 that Arkansas presented “the best opportunity to bring a U.S. lithium project online and into production faster than anyone else.”

The lithium in the Smackover Formation—which may come from old volcanic ash, or may have migrated upward through rifts—is not a rock that can be strip-mined, like gold or graphite. Instead, the element dissolved within the saltwater “brine” that lies inside the pores in the limestone. Most commercial operations across the world produce lithium from brine with evaporation ponds: the pumped-out brine is set at the Earth’s surface to evaporate. It’s a slow and wasteful process, consuming as much as 200,000 gallons of water as long as two years to produce one tonne of lithium.

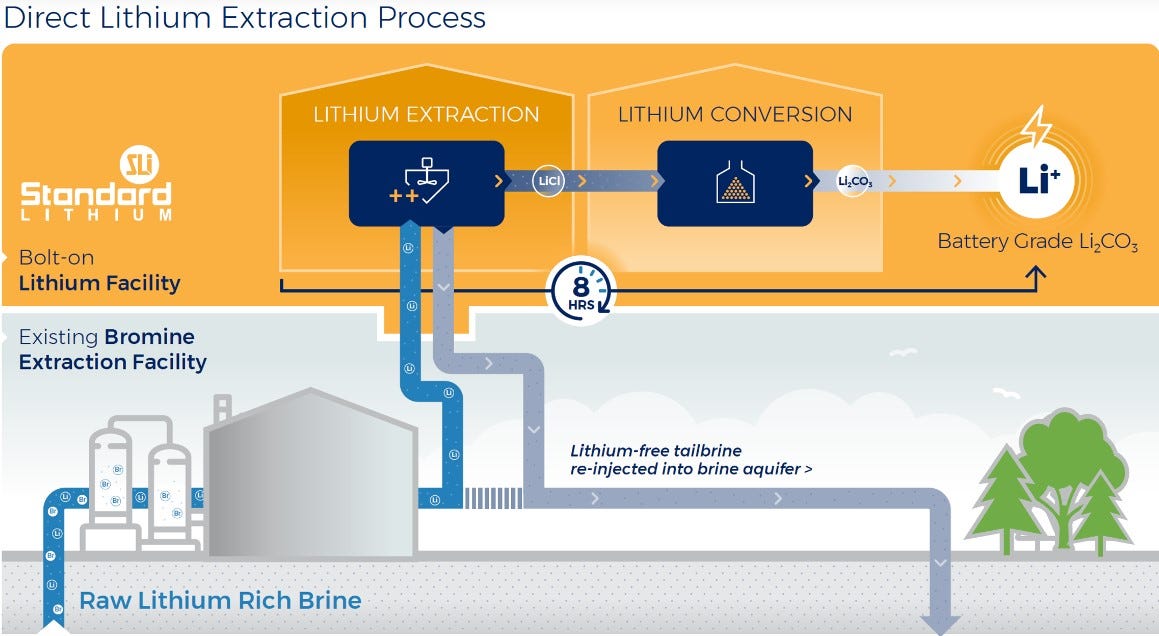

It’s a process that wouldn’t even work in Arkansas if companies wanted to try it, since oilfield brines have lower concentrations of lithium than “continental” brines found in deserts—and, besides, it would be hard to dry the ponds in swampy southern Arkansas. In Arkansas, companies are proposing a newer and higher-tech process known as “direct lithium extraction,” in which the water will be treated to remove the lithium, then pumped back underground—no ponds at all. The ecosystem effects of this process are not totally clear, since this is a new approach, but it should at least consume less water than evaporitic extraction.

So the mayor of Magnolia, Arkansas—a town near Smackover, where ExxonMobil plans to build one of the world’s largest lithium production facilities—is preparing for the latest boom. Along with two other proposed lithium projects, the plant could bring 6,000 new jobs to Magnolia, a town of just 12,000—which lacks the homes and roads that are needed.

“No one is listening right now,” the mayor told the Journal. “But when it blows up, it’s going to be too late.” Let’s hope, at least, that it’s a bit more tame than the boom a century past.

Around the Southlands

Ocean temperatures in southern Florida are now as warm as a hot tub, the Associated Press reports—which could devastate corals and worsen hurricanes.

The Southern Environmental Law Center has filed notice of its intent to sue the U.S. Forest Service over its management of the Nantahala and Pisgah national forests in North Carolina, WRAL News notes. Among other issues, the SELC alleges that a proposed forest management plan fails to sufficiently protect endangered species.

The most common explanation is, as it happens, ecological: some histories suggest that in the eighteenth century, the French described parts of southern Arkansas as “sumac couvert,” or covered in sumac bushes. The name was then Anglicized into Smackover.